Musicologist Melanie Unseld talks about the legacy of singer and drawer Celeste Coltellini – and what it says about the classical music scene in the period around 1800.

QUESTION: Celeste Coltellini was a famous singer in her time. She lived from 1760 to 1828 and was part of Vienna's classical music scene in the period around 1800 that we now associate so heavily with Mozart. But Coltellini was not just a singer, she also made a lot of drawings. Researchers have now been given access to her artistic legacy for the first time. What exactly does that legacy comprise?

UNSELD: At the core is a particularly interesting collection of six sketchbooks. The family, which so generously gave me access to the legacy, always made a point of documenting the fact that its female members had been artistically active across several generations. Celeste Coltellini was one of them. We have now been able to evaluate her sketchbooks. Carola Bebermeier, a doctoral candidate in my department, wrote her dissertation on the subject.

QUESTION: Can pictures also serve as musicological sources?

UNSELD: Yes, absolutely. But this requires an exchange between disciplines. Here at the University the work on the theory and history of art is highly advanced and raises new questions about approaches to visual culture. It is based on the premise that the visual is not immediately evident, but rather that images "allow something to be seen". However, they can also conceal things. It is an approach that doesn't aim to fully interpret pictures but to see them as part of the cognitive process. This is also productive for historical musicology because here too, it is important not to use pictures in a purely illustrational way but to see them as valuable in their own right.

QUESTION: And you are using this approach with the sketchbooks too. What significance does this discovery have for your research into music history?

UNSELD: The sketchbooks provide insights into the very specific music culture of the period around 1800. Coltellini was very well connected – and we are given glimpses into her everyday life as a singer and cultural mediator because for a long time she was a prima donna in Naples, and she also performed in Vienna. Inspired by musicological gender research we ask: what really means “music”, and what means “musical culture”? Because the sketchbooks reveal a very different assessment of the importance of the people who were active in this environment. The focus is not on the composer but rather on the opera as an event in which many different people participate. So here we see that the opera phenomenon is not confined to the actions of famous composers, but that those composers are active within a whole group of people. Music is therefore more than just what the composer puts down on paper.

QUESTION: Can you name an example?

UNSELD: There is one drawing by Coltellini which shows the composer Giovanni Paisiello listening to Coltellini singing as she sits at the harpsichord. Another unidentified person is also listening. But in this picture the composer is part of a sphere of activity in which the singer plays an equally active role. And that is the point here: not to focus on the work but on the event, whether it's a rehearsal or a stage performance in which everyone plays their part – the singers, the conductor, the composer, the librettist, the impresario who makes sure everyone does what they are supposed to, the stage hands and so on.

QUESTION: Did Mozart and Coltellini ever meet?

UNSELD: Yes, and there is proof of it. Celeste Coltellini was an opera buffa singer. For ten years she was the undisputed prima donna in Naples. Joseph II, however, was always on the lookout for talented singers for his Viennese stages and he brought her in straight from Italy's best stages. So Coltellini came to Vienna and her first season there was very successful. She was also in Vienna for a second season, but it was less successful. The precise circumstances are a little unclear. She arrived late in the city and missed some rehearsals. The sources don't provide sufficient details. But we do know that the two were in contact with each other during that season because Mozart composed for Coltellini.

QUESTION: What do you mean by that?

UNSELD: The event of opera staging in 18th century never entirely goes out from the score. It was the singers, and above all the primo uomo and prima donna, who had a great influence on what was sung. This was because on the one hand the parts were specifically written for particular singers by the composer, and secondly because the singers were allowed to add their own arias to an opera, which meant that composers constantly received requests to compose them. Coltellini also came to Mozart with such a request, and he composed several ensembles for operas that she performed in Vienna. But in order to write those parts for her he would have to have been very familiar with her voice. So they did meet. And perhaps Mozart – like Paisiello – even sat next to her at the harpsichord.

QUESTION: Do the sketchbooks make any reference to this meeting?

UNSELD: One of the sketchbooks was used by Coltellini while she was working in Vienna for the second time. And that book contains the address of the house where Mozart was living at the time. Mozart had rented a house out in the country for a few months. Today, of course, that area is within the city. But back then it was a little outside the city. Such accommodation was therefore more affordable and spacious.

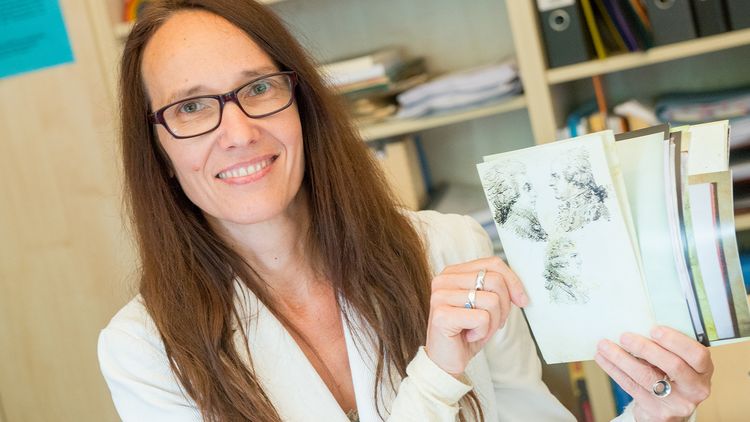

QUESTION: Did Coltellini make any drawings of her meeting with Mozart?

UNSELD: Her Viennese sketchbook contains many pages featuring several heads in profile. Sketched encounters. One of those pages shows a profiled head which, according to the family tradition, is a portrait of Mozart. We examined the issue more closely and found indications that support that assumption. Leonhard Posch was a famous medallist at the time who made the so-called "Gürtelschnallenrelief" of Mozart. The similarities between Coltellini's drawing and that relief are remarkable. This and other indicators suggest that it is indeed Mozart in the drawing. But ultimately we can't prove it.

QUESTION: Which is presumably not such an important aspect for your music historical research?

UNSELD: Precisely, this is just one small picture in a very large assortment of drawings. If we were to focus solely on the question of whether it really is Mozart, Coltellini's role as a representative of her times would retreat into the background again. Perhaps it is a portrait of Mozart. We have good reason to believe so. But even if we could be sure, naturally it is not Mozart but a picture Coltellini drew of a musician she met in Vienna. So the question of whether it is a picture of Mozart is the wrong one to direct at this source.