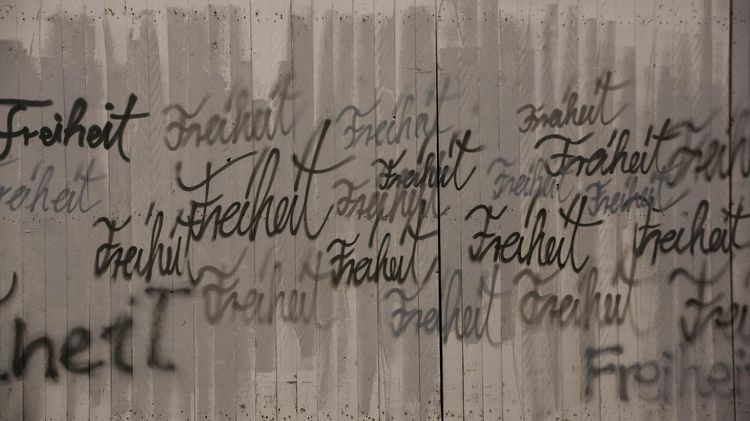

A value of modernity

A value of modernity

A value of modernity

In our interview, philosopher Tilo Wesche talks about the limits of freedom and the prerequisites for voluntary social and political participation.

We are currently witnessing people risking their lives to defend the freedom of their country. Why is freedom so valuable to us?

Modernity defines itself precisely by a gain in freedom. This is evident in the history of ideas, but also in our daily life: for young people, the most important thing is to be independent – whether it's climbing a jungle gym as a small child or or going into town on their own when they grow up. And it is also very important for older people to maintain their independence and to move around autonomously.

However, in our daily routine, we are wrapped up in duties, for example at home or at work. Are we actually free after all?

To think that we are only free when we are completely free from everything would be a liberalist misunderstanding. After all, there are two basic meanings of freedom. The first is negative freedom, being free from something. The second is positive freedom, being free to do something – that we can give ourselves purposes, as Kant put it. In our daily lives, we are indeed determined by many circumstances. But often these routines are based on self-chosen purposes, so in a way they make us free. Freedom is therefore compatible with many things that at first glance seem to contradict it. But if you say that freedom is primarily independence and secondly, an exclusive value – the only thing that counts – then you can quickly get the impression: I am permanently determined by others.

When people say they feel like living in a dictatorship because they are obliged to wear masks or to be vaccinated, which idea of freedom is behind this?

They understand freedom in an absolute way. In fact, however, freedom is not a value that stands alone. Rather, it must always be considered in context. It should always be compatible with norms or values that in some way oppose it, for example equality or solidarity. Kant was already considering how to reconcile equality and freedom, how to reconcile domination and freedom. We have certain duties for good reasons. It is a complete misunderstanding to think that everything that obliges me threatens my freedom.

You work in a research group on Voluntariness funded by the German Research Foundation. Your project examines the way the term is sometimes misused. Can you give any examples of this?

When we refer to "voluntary" with regard to political and social engagement, the use of the word is justified. We take part in democracy on the basis of voluntariness. That means we voluntarily vote in elections. We inform ourselves voluntarily. We also organise demonstrations voluntarily, if necessary. But sometimes, the term is only used as an excuse. This has happened, for example, in debates about food labelling. Other examples include the introduction of animal welfare standards or a female quota in the boards of DAX-listed companies. The term "voluntariness" is then, in a sense, only a rhetorical means to prevent legislative measures. In the end, nothing happens.

Our free, democratic society depends on people voluntarily participating in political processes. Isn't that a contradiction?

In a way, yes. Democratic participation should be voluntary. We should not be obliged to inform ourselves or to vote. But it is important to see that this voluntariness presupposes certain conditions. So, we must not draw the conclusion: Those who do not participate, those who belong to the group of the so-called politically apathetic, only have to be willing.

Which conditions can encourage people to participate?

First of all, quite clearly, a certain legal security and educational opportunities. But we also need free spaces for communication and culture. In these spaces, it should not be important to meet expectations and to achieve a result. In this special kind of communication, a conversation is not held in order to pull the other person over to one's side, but to discover what is true and what is not through a free play of arguments. Many things can happen in such conversations: Your own convictions can take a different direction, sometimes you succeed in opening your eyes to new arguments and points of view. These are all very important requirements for developing a willingness to participate voluntarily in the first place.

Where can you find such spaces?

I think it is an important function of universities to provide these kind of spaces. It's crucial that the focus there is not on education and exams or on achieving a certain professional goal, but that we have these areas of freedom beyond any pressure towards exploitation.

What does freedom mean to you personally?

Above all, the joyful feeling of living in a democracy – especially now, in view of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I also remember a very personal experience. When I learned to ride the bicycle as a little boy and my father let me go and I was able to ride myself for the first time – that was a very elating feeling of freedom.

Interview: Ute Kehse