Power to the people

Power to the people

Power to the people

How can local initiatives find ways to provide themselves with clean energy? Within the EU project COBEN, led by Thomas Klenke and Gerard McGovern, experts work on finding new solutions.

Using the waste heat of a factory locally or enabling electromobility in rural areas with surplus electricity – these are examples for possible solutions sought within the COBEN project. The project, which is supported by the European Regional Development Fund, is concerned with concrete approaches to enable local stakeholders to shape energy change on their own responsibility. A major challenge is to embed climate protection in communities by creating new energy infrastructures while at the same time combining this with other local development goals.

“We want to enable communities to generate and consume energy independently and set up efficient structures to do so – from energy sources to energy generation and marketing,” says Dr. Thomas Klenke. He and his colleague Gerard McGovern at the university's Centre for Environment and Sustainability (COAST) are heading the project.

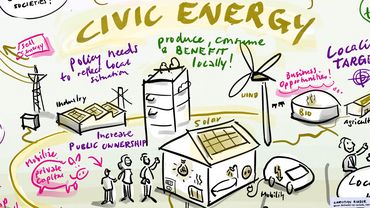

By setting up local energy initiatives, the six regions participating in the project in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scotland and Denmark are pioneering a transition that has only just begun at the European level. “Civic energy” is the name of this approach, for which the European Commission paved the way in May 2019 with its latest decisions on the legislative package “Clean Energy for all Europeans”.

Genuine alternative to traditional energy supply network

Under the new legislation, energy producers and consumers will no longer have to follow the specifications of major power grid operators. Instead, they will be able to generate, store and distribute electricity and thermal energy independently. This has not been possible until now, for legal as well as other reasons. “Civic energy thus offers a genuine alternative to the traditional, centralised energy supply network,” McGovern, the project coordinator, explains. “That’s pretty revolutionary.”

This brings the scientists in the COBEN project closer to one of their goals, which is to ensure that ultimately communities and the people who live in them benefit from the results of the energy transition. The idea is that the added value and thus the financial revenues remain within the community. “But that’s easier said than done,” says McGovern.

This is why the participants in the six pilot regions first of all work out the requirements of each community: How much heat or electricity do they need? What about mobility? What are the potential energy sources? And what are the advantages for communities of setting up their own value-creation cycles for energy?

Communities themselves become drivers of the energy transition

“What’s special about this is that we are combining the energy transition with other goals in community development,” says Klenke. “But the focus is always on the people”. The Danish municipality of Ringkøbing-Skjern, for example, has set itself the goal of covering all its energy needs from renewable sources by 2020.

The advantage in this windy region is that wind power already generates more electricity for the community than its companies and residents actually need. “The Danish partners are now looking at how they can use this surplus to secure further advantages for rural structures," McGovern explains – for example a new local transport system that is not dependent on fossil fuels.

This example shows how the entire community can benefit from the goals of the project, says Klenke. “The advantage is that communities themselves become the drivers of the energy transition.” The task of the Oldenburg scientists is to draw general conclusions from the six regional initiatives. To do this they outline the various processes that are necessary to implement the structural changes for paving the way to climate-friendly communities.

Results have been incorporated into the amended EU resolution

This will gradually result in a roadmap for civic energy. In addition, the researchers will summarise their findings from the case studies in twelve different business models with the aim of encouraging other regions to follow suit. “The most important aspect in this process is that communities or regions clearly define their social, societal and environmental development targets from the beginning,” McGovern emphasises.

Ultimately, COBEN aims to put the energy supply process back into the hands of communities – independently of the control of big energy companies and network operators, the researchers explain. Naturally there are still technical challenges ahead, such as the creation of local networks, Klenke stresses. He points out that new decentralised structures could take over tasks of centralised systems, for example.

The idea of producing and distributing electricity in new ways also has to be financially attractive, he adds. But the work has begun: “As a project partnership we are quite proud that the positive interim results of our project have been incorporated into the amended EU resolution,” he says. Now the EU member states must implement the new directives into national law. Klenke and McGovern hope that the concept of civic energy will not be watered down in the process, so that efficient, community-run civic energy systems can become a reality.