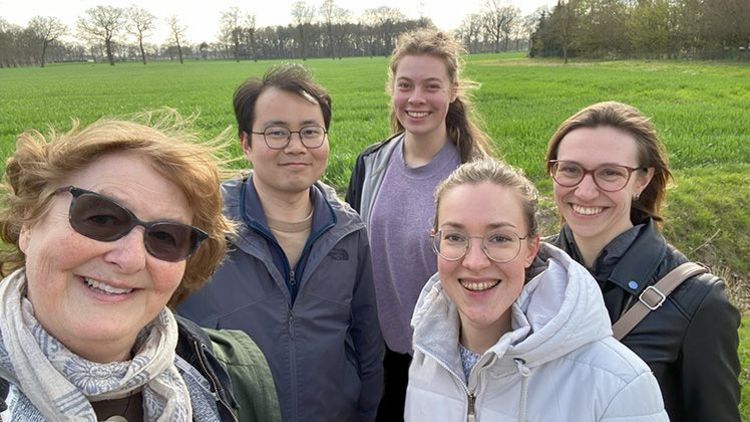

In April, Canadian scientist Kim Baines paid a visit to the Institute of Chemistry. The recipient of numerous awards, including the prestigious Humboldt Research Award, discovered a new class of compounds made of silicon and germanium which is now used by researchers around the world.

A research stay at the University of Oldenburg's Institute of Chemistry is "better than a conference", says chemistry professor Kim Baines. "You have a lot more time to exchange ideas with colleagues," she explains. Baines, who holds a Distinguished University Professorship at the University of Western Ontario in Canada, has made the most of that time in April. She dropped by to have a chat with each of the doctoral candidates in Professor Dr. Thomas Müller's Inorganic Chemistry research group about their projects, for example. "It's always good to talk to a multitude of people because you can pick up new ideas and get feedback on your own work," says the chemist.

Baines has spent several weeks with Thomas Müller's research group. In 2015, she received the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation's coveted Humboldt Research Award, which honours leading researchers from outside Germany for their academic achievements to date. The winners of the award are invited to conduct a research project of their own choosing with expert colleagues at an institution in Germany.

Baines picked Müller and his research group back then because they both work with similar compounds: the two scientists are conducting basic research on highly reactive compounds of the main group elements silicon and germanium. "What attracted me was the combination of experimental chemistry and computational chemistry that the Oldenburg research group is doing," says Baines, who visited Oldenburg four times since winning the award, and also works with researchers in Berlin and Saarbrücken in the context of her Humboldt project.

"I love Oldenburg"

The Canadian scientist stayed in Oldenburg until the end of April. "I love that everything is so close together here. Whenever I visit I always stay in the city centre," she says. Oldenburg is similar in size to London, her hometown in Canada, but whereas everything is very spread out over there, many interesting destinations are within easy reach by bus or train from Oldenburg, Baines explains.

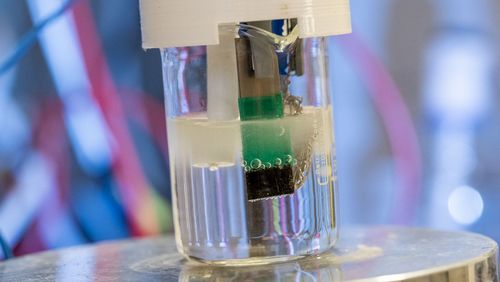

But for excursions to places like Lübeck, Bremerhaven or Lüneburg she only had time on the weekends. The main focus of her stay was research. She and Müller are currently investigating a key reaction in a class of silicon compounds known as disilenes, with the aim of gaining a better understanding of the intermediate steps so that these inorganic compounds – which consist of two silicon atoms with a double bond between them – can be used in future applications. "Disilenes and similar compounds, the silenes, are the inorganic counterpart to alkenes, which are unsaturated carbon compounds," she explains. But while alkenes are the most important base materials in the chemical industry – they form the basis for plastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene, for example – there are hardly any applications for disilenes at present.

This hasn't diminished Baine's enthusiasm for this substance group in the slightest, however. "They have huge potential, for instance as new materials or catalysts that don't require precious metals," she explains. But silenes are far more difficult to work with than alkenes: "It's nowhere near as easy to make polymers from them," she explains, adding that research on the chemistry of disilenes is "a hundred years behind" that in the field of organic chemistry. "It took us a long time just to make them. Now we need to understand the reaction pathways," she says.

A new class of compounds

Baines is also interested in compounds made with germanium – an element with similar properties to carbon and silicon. It is largely thanks to her that the potential of these substances is now being recognised. She "pioneered the synthesis and chemistry of germasilenes and novel low-valent germanium, tin and gallium cations, opening new areas of scientific inquiry," the Royal Society of Canada wrote when it named Baines a Fellow in 2022.

"There are always a million things to do, but one only has so much time," Baines observes with a chuckle. But even so, she can look back on a diverse career: in addition to her numerous research projects she served two terms as department chair and was also assistant dean at her university in Canada. And for several years now she has campaigned for groups that are underrepresented in the field of chemistry, including women, Black people and Indigenous peoples in Canada. "These issues are very close to my heart, even though I'm no expert on them," she says.

Her impression is that Canada is a little further ahead than Germany in this respect. "Nonetheless, when it comes to practice, not much changed in the first 30 years of my career," she observes. And despite important advances in the last five years, there are still systematic barriers, such as unconscious biases, that hinder genuine equity of opportunity, she explains. "No one is immune to this, including myself," she admits. Which is why it is all the more important to be open about this and keep questioning your own attitude, she adds.

But there is one area where she definitely sees progress: it's far easier for female academics to start a family today than it was in the 1980s and 1990s – also in Germany. "Things have really changed since I was a postdoc at Dortmund University for a year in 1988," she notes, adding that back then, female researchers who wanted to have children wouldn’t even have considered an academic career. For Baines, however, it was always clear that she wanted both – a family and a career in science. "People said I was crazy, but in the meantime women of my generation have shown that it works."

Her main piece of advice to young women academics is: "Follow your passion!" People are always happiest if they can do what they enjoy doing, she observes. Her own passion for basic research has never waned. "I retire in June, but I would like to finish the joint project with Professor Müller before that," she says. The chances are good: their third joint paper has just been published.