A count's captured clothing

Author / Contact

Justin Schröder is a research student in the Prize Papers project team alongside his Master's studies in History and German Studies. His guest article first appeared on the project website and is based on his bachelor thesis „Ich packe meinen Koffer” ("I'm packing my suitcase").

A count's captured clothing

A count's captured clothing

An invitation to celebrate with the British king - as it may soon reach some for the coronation of Charles III - and the noble wardrobe gets lost on the journey? History student Justin Schröder describes how the finest silk stockings and silver lace collars were caught up in the mills of justice in 1745.

Imagine that you are invited to an important celebratory event, an exhibition opening or a event with a hand-picked audience. But what do you wear? Even today you would be expected to wear something appropriately elegant. After much deliberation you find the perfect outfit.

But how do you feel if you cannot find the carefully chosen garments you ordered just before the event? Presumably similar to how Count Josef Xaver von Haslang, Privy Counsellor and member of the Order of St. George, must have felt in 1745 when he found out that his garments, which had been ordered for King George II’s birthday party were captured en route from the European mainland to London.

And, as if this was not enough bad luck already, the sources – used for the very first time for my Bachelor’s thesis – show that the clothes were confiscated by the Crown, which must have been particularly annoying for Count Haslang, who served as an envoy from the Electorate of Bavaria in the diplomatic service at the English royal court.

Now began a race against the clock: the diplomat had less than three weeks to procure the clothing especially ordered for His Magesty's Day from a warehouse owned by the English Crown. But why did the English Crown confiscate a diplomat’s clothing? The explanation can be found in the logistics of delivery. Count Haslang commissioned a merchant friend to buy certain items of garments in France. His friend bought the items ordered on site and set off by sea towards Rotterdam. On the way from France to Rotterdam, the ship encountered the English privateer Charlisle, which captured the supposedly hostile French ship as prize.

This capture, which was extremely unfortunate for Count Haslang, turns out to be a great stroke of luck for researchers today. The court documents on the individual captures housed today in The National Archives (TNA) in London allow a glimpse into the festive wardrobe of this noble count.

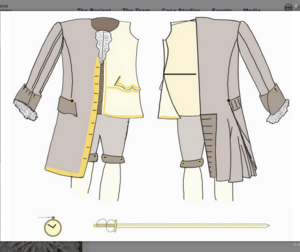

Yet why focus on the Count’s wardrobe? Garments serve as a non-verbal medium of communication and at the same time as status symbols. They can also be an expression of prevailing social norms and conventions. This demonstrates the possibilities that research into materiality and garments can open up to historians. If you look at the documents and lists of confiscated garments and accessories of the count, it quickly becomes clear why he specifically insisted on the clothes he had ordered. His clothing consisted of fine silk stockings (forty-eight pieces in total!), a justaucorps (cloak), a jabot made of silver lace and other items.

In addition to the items of garments mentioned in the inventory lists for the court, conclusions about his garments can also be drawn from archived personal documents of the count. For example, the Count's written language and omnipresent titles indicate the position he held in society. This in turn influenced the sartorial and material aspects of his clothing. Sources can be found that refer to the use of diamonds and jewels as buttons by diplomats in the eighteenth century. Other accessories such as a pocket watch or a sword were worn to underline status. These items were considered indispensable status symbols at the time.

All in all this shows again how much can be learned from everyday objects, such as a stolen wardrobe. The research on Graf Haslang’s clothes are possible because of these unique sources held at the TNA in London, demonstrating the importance of the Prize Papers Project.