When letters act for their author

When letters act for their author

"Being able to zoom in and zoom out again is simply fascinating," says historian Lucas Haasis about microhistory. In such a micro-historical study, he himself has just spent about ten years investigating a sort of time capsule.

A merchant’s archive from the 1740s was the focus of his dissertation project. "My starting point were the contents of a wooden travel chest, which are stored in their entirety in three of the more than 4,000 archive boxes in the collection. I read and transcribed everything, and then used this as the basis of my analysis," Haasis explains. His focus was on the letter-writing and business practices of Hamburg merchant Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens. Through the letters, Haasis was able to follow how Luetkens, who was travelling in France at the time, founded his own merchant house and prepared his marriage – "all through the medium of letters", as the historian emphasizes.

Luetkens' correspondence was one of those chance discoveries. Haasis has been a member of the Oldenburg Prize Papers team since the preparatory phase of the project before its official launch in 2018. He was on his second visit to the National Archives when he came across several boxes full of documents seized from the Hamburg merchant ship Die Hoffnung. Haasis describes them as "a time capsule, whose contents were unknown". He took lots of photos so he could read the documents in peace at home. "It was only then that I realized this was a complete archive of letters, and that it all belonged to the same guy!" Galvanized by his discovery, Haasis rushed back to London and "took photos of everything".

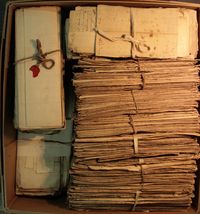

"Everything" comprised a complete business archive in which Nicolaus Luetkens had kept all incoming letters and a letterbook with copies of all outgoing letters produced over the course of his two-year business trip along the Atlantic coast. More than 2,400 letters in total had been stored by Luetkens in the wooden travel chest, as well as invoices, outstanding bills of exchange, newspapers, and items of clothing. As Haasis later learned from the court documents, this wooden chest was hidden under a stack of barrels of sugar in the hold of the Hoffnung when the ship fell into the hands of privateers on August 23, 1745, on its way from Brest to Hamburg. Now the historian knows: "Luetkens had sent this letter archive, his main asset, to Hamburg with the intention of opening his merchant house there after two years of preparation – and then he lost it all. That's the equivalent of losing a computer together with all the passwords and company secrets today."

But Luetkens' loss is a huge gain for scholars researching the history of letter-writing and business practices. The documents enabled Haasis to not only reconstruct the merchant's journey all the way from Bayonne in the south of France to Brest in the north. Moreover, the historian could observe his practices and tactics throughout the entire process of establishing his merchant firm. And what practices they were! "What we see here are intrigues; how he exploited legal grey zones and used insider trading tactics. Few other mercantile records known to date offer such insights!", Haasis points out.

The documents also include personal letters, such as letters to Luetkens' future wife Ilsabe Engelhardt. It's "an absolute privilege", Haasis says, to be able to conduct research on such unique documents. Especially since many of them remained untouched for so long. For the conservators, archivists and photographers in London as well as the team in Oldenburg, preserving the documents in their original historical state is a key priority.

Anyone who will read Luetkens’ digitized letters in the Prize Papers online portal in the future will also find long-winded, at times pompous-sounding declarations of love, which Haasis’ analysis revealed to be set phrases taken from the letter-writing manuals popular at the time.

At the end of 1744, Luetkens sent jewellery and other such "trifles" to his "most beloved" to console her for his having to extend his journey. The collection also includes letters securing the financing of business deals or assuring a ship's crew that he would pay a ransom if they were captured in the Mediterranean Sea by privateers of the Ottoman Empire. "The letters spoke, indeed acted on behalf of their author," says Haasis. On May 5, 1744, Luetkens penned the following lines to his brother Anton:

Since (...) the turmoil of war has given some people reservations about loading cargo onto our ships (...), I had the idea that you should become a citizen (...). Then I would sell you a share in the ships so that you could swear in good conscience (...) that they belong to you.“

Being in France, which was at war with England, Luetkens had decided to use his brother as a straw man so that his ships could sail under the neutral flag of Hamburg and thus avoid being captured as "prizes". However, at least in the case of the Hoffnung, this strategy failed.

But despite such setbacks, Nicolaus Gottlieb Luetkens succeeded in founding his own merchant house in Hamburg, married his fiancé in 1745, and even went on to become a senator of the Hanseatic City. His Beletage – the luxury entrance hall of his villa with its French gilt furniture – can still be admired today in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, the museum of arts and crafts, in Hamburg.

This text is a revised excerpt from the article "Snapshots of the Past", first published in the 2021/22 issue of the research magazine EINBLICKE. Author: Deike Stolz