Injustice with continuing impact

Photo exhibition in Berlin

The photo exhibition "Prize Papers and Transatlantic Slavery - Exploitation, Suffering and Injustice Committed" can be seen at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities until March 31, 2024.

Address: Academy building at Gendarmenmarkt (entrance Markgrafenstraße 38), Berlin. The Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities is sponsoring the exhibition. It was curated by Maria Cardamone, Dr. Lucas Haasis and Dr. Oliver Finnegan (advisor: Dr. Misha Ewen, collaboration: Lisa Magnin).

Injustice with continuing impact

Some 12.5 million enslaved people were shipped from Africa to the Americas in the early modern period – one of the greatest crimes against humanity. The academy project "Prize Papers" visualises shipping routes, human fates and Europe's deep involvement, now also in cooperation with the renowned "Slave Voyages" project and its database. Excerpts from a talk given by historian Lucas Haasis.

Drawing the routes of captured ships from the Prize Papers collection on a world map illustrates the global dimension of this unique collection of documents and the academy project. In many cases, these routes are linked to the Atlantic Slave Trade, the triangular trade in enslaved people. Thousands of people were trafficked by the colonial powers at the time – primarily by France, England, the Netherlands and Spain – and many of the captured ships, whose routes and cargo the Prize Papers bear witness to, were involved in this trade.

These ships transporting enslaved people were also captured as prizes during the naval wars, and documents and artefacts were seized from them and used as evidence in the consecutive court proceedings. We have just published extensive material from two ships involved in the slave trade for the first time. These are several thousand documents that anyone interested can view open access – and documents and artefacts obtained from more ships will follow. In future, these documents from the Prize Papers, which originate from captured ships that were involved in the slave trade, will also be available in the international database of the "Slave Voyages" project, with which the Prize Papers team has recently started co-operating. Moreover, the Prize Papers project is currently presenting selected examples of documents and objects in large-format photographs in an exhibition in Berlin.

In the trials before courts of the high admiralty, slavery was not condemned, but negotiated – with enslaved people treated like any other goods. Because of the prize-system, sailors who had captured a ship and its cargo could claim ownership of the enslaved people on board. For example, a British commander would argue that these people were part of a legitimate 'prize'. If the court later ruled the capture was legal, the enslaved people were declared "enemy property" and sold at auctions. Few documents mention enslaved people by name and only in exceptional cases did they have their say in court.

With the current exhibition, we aim to draw attention to the fate of these enslaved people and the crimes of the slave owners. Transatlantic human trafficking and the plantation system are among the greatest crimes against humanity. And the consequences of this injustice are still with us today: inequality between the global North and South and racism against black people – the topic is also topical in current politics and public debate.

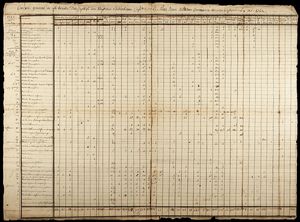

The Prize Papers provide direct insights into the business with and exploitation of people. The bookkeeping on board reduced the abducted people to numbers, rendering them nameless and thus glossing over the barbaric practices of the slave trade. One example: a table on board the French ship "Abraham de Nantes" records the 304 men, women, and children that the crew bought in various harbours on the way from Monrovia in Liberia to Ekpe in Benin – and meticulously noted the quantity of wine, fabrics or cowrie shells that were exchanged for the people.

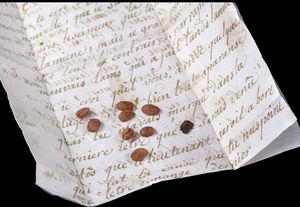

People were also bought in exchange for colourful glass bead necklaces, known as slave beads, for example in Elmina Castle in present-day Ghana, a Dutch trading hub that mainly sold enslaved people for onward transportation to America. Artefacts such as glass beads have also been preserved in the Prize Papers – for example a glass bead necklace that was on its way from Elmina to Amsterdam as a sample for future orders in 1803, when the ship "Diamond" carrying this letter was captured.

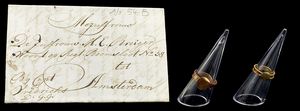

Glass jewellery of this kind is still worn in Ghana today and carries a high emotional value, as we were able to learn from the Ghanaian researcher Sarah Tam. It is important to contextualise these artefacts. The same applies to two gold signet rings that have been preserved in unopened letters in the archived captured goods from on board the "Diamond".

These rings are in remarkable condition for being over 200 years old – they look like new. The sealed accompanying letter in which they were enclosed contains important details about the jewellery. The author, J.G. Coorengel, writes from Elmina to his mother in Amsterdam. To comfort her after her father’s death, he sent her the locally made rings. They were made by Ghanaian artisans who were most likely enslaved.

In exchange for enslaved people, colourful printed cotton fabrics were also a sought-after commodity. The Prize Papers contain samples that Dutch merchants sent from plantations in Surinam to Amsterdam. The fabrics printed with motifs were popular as barter currency in the slave trade and also in European trade. On special occasions, enslaved women in Surinam who worked in the house wore elaborate dresses made from the same fabrics, according to historian Hilde Neus of the University of Surinam.

The Prize Papers collection at the National Archives in London also contains single-colour but no less relevant fabric samples from other sources, such as those from letters from the Moravian Church: They show that religious groups were also involved in plantation slavery. Letters from Moravian tailors in Surinam, for example, contain fabric samples that were actually on their way to Saxony along with other captured goods.

The textile industry in Saxony, Thuringia and Silesia also supported the transatlantic slave trade by supplying fabrics that were used as clothing for the enslaved people on the plantations. For example, the Moravian tailors' workshops in the then Dutch colony of Surinam trained enslaved people as tailors, who could be paid in cloth. This shows once again that it was not only the colonial powers that were responsible for the trade in and abduction of enslaved people from Africa, but also German merchants, for example.

Another find that sheds light on one of the many human fates is a basket in which the captain of the ship "Le Printemps", captured on its way from present-day Haiti to Bordeaux in 1747, kept his personal archive of letters. The basket was found wrinkled and creased in the National Archives in London before our curator Camilla Camus-Doughan restored it to its original form. The handmade basket has knotted hair handles and a mud-painted frieze. The craftsmanship and tradition evident in this basket suggest that the maker – most likely an enslaved person – was from Gambia, Senegal or Mali.

First-hand accounts from enslaved people are very rarely preserved in the archives – but they do exist. For example, while researching trial records from the Prize Papers collection, we came across "Caesar", who was born into slavery in Maryland, as he himself stated on the record. When British privateers captured the ship "Priscilla" sailing under the flag of the "secessionist" colonies during the American War of Independence, Caesar was on board. The New York Vice Admiralty Court took his statement, and as he could neither read nor write, Caesar signed it with an x, next to which is the note "Caesar his mark".

Although slavery was outlawed in Europe, it was possible to circumvent the ban. For example, a document signed by the French governor of Martinique allowed for an enslaved ten-year-old named "Scaramouche" to be shipped to France. The name was given to him by his owner; his real name is unknown. But we do know from the document that he came from the kingdom of Arada in Benin. According to the letter, the boy was destined for the widow Charron in Nantes, who wanted to "teach him a trade and educate him in the Catholic religion" before sending him back. His fate, especially after the capture of the ship, remains unknown.