Aging and old age affect everyone. Geriatrician Tania Zieschang and philosopher Mark Schweda approach the topic from different perspectives. An interview about protecting the elderly in the pandemic, robots in care – and what stays with us.

Professor Zieschang, like virtually all organisms, humans age. When does this process begin?

Zieschang: In some respects, it begins at birth. By the time we’re 20, at the latest, changes can be detected at both the cellular and molecular levels. The telomeres – the ends of our chromosomes – become shorter, cells undergo changes, certain metabolic products accumulate. So we see signs of aging in young people too. It starts pretty early on.

Many disciplines, from biology and psychology to the social sciences, study the phenomenon of old age and aging. How do you – a geriatrician and an ethicist – view old age?

Zieschang: First of all, we have to be clear about how heterogeneous the older generation is – far more so than younger age groups. There are 80-year-olds who are still running marathons or learning new languages, but at the same time there are 70-year-olds who are completely dependent on care. As a geriatrician, my focus is on people who need a high level of support, whose independence is at risk or already restricted. This is particularly the case among the over-80s, but there are also people in their seventies who are multimorbid – in other words, those who suffer from more than one chronic illness.

So your main criterion is the need for support?

Zieschang: Precisely. Naturally we can all suddenly be confronted with the loss of independence due to an accident or serious illness. However, I’m talking about patients who can be plunged into a downwards spiral by a minor infection or alteration. The reserves – even in an 80-year-old marathon runner – just aren’t what they were in youth. It is this vulnerable and highly heterogeneous group that we focus on.

Schweda: Aging is indeed a complex and multidimensional phenomenon. First of all, it’s a basic calendar fact: as time goes by the years accumulate, and this changes – quite literally – our standpoint in life. So in addition to the already mentioned functional aspect, aging is also a psychological and mental process: something happens to us, our perception of things changes. And finally, aging is also a social phenomenon. Whether we count as old or not is decided, not least, by others. In modern industrial societies, the threshold to old age is retirement. In the past you were given a golden watch and sent home to sit in your armchair and wait. For what? For death! For a long time, this was the role that older people were given.

A socially defined role.

Schweda: Cultural ideas are key here – the images we have in our minds. Quite often these are very negative and focus only on deficits. Medicine is not entirely blameless here. If you look at an aging person from a medical perspective, the first thing you see are physiological degradation processes, dwindling reserves and declining performance. Yet from other perspectives, aging has much more positive connotations. In the philosophical tradition, for example, aging is often associated with wisdom, with a life experience that gives you a view of the bigger picture and more insight. The fact that nowadays we perceive aging mainly from a medical perspective is on the one hand important, because a lot can now be done about age-related impairments and diseases. On the other, however, there is the risk that aspects of old age are themselves increasingly perceived as diseases.

Zieschang: In geriatrics and in medicine in general, we are seeing a certain shift away from this purely pathology-oriented deficit model and increased focus on the process of creating and maintaining health, also known as salutogenesis. This is a way of thinking that I happily offer my patients: that it’s actually a miracle that our organism regulates itself over decades despite all the disruptive factors. A huge effort that we barely perceive goes into achieving this balanced state known as homeostasis.

So you deliberately focus on the resources.

Zieschang: We have integrated this approach into our work in geriatrics. In team meetings we make a point of describing all the things a patient is still capable of doing, and the potential that is there. We also look at how the social environment can be used as a resource to help the patient in the future. That changes a lot in people’s minds. However, I admit that we geriatricians also tend to relapse into the deficit mode of thinking. Medicine starts from the premise that good health is the normal state, and society from the premise of the perfect face with smooth skin, in which wrinkles are seen as flaws. A study has shown that people whose perception of old age is shaped by negative stereotypes have shrinkage of the hippocampus. This is the region of the brain that first undergoes changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, a longitudinal observation study showed that people with a negative attitude towards old age have a significantly higher risk of dementia. So it seems to be also up to us. One hypothesis: If, as a society, we focus more on the advantages of aging, age-related cognitive decline could be considerably reduced.

What’s your view on this, Professor Schweda? You did a research project on the idea of “successful aging“ from a normative perspective …

Schweda: The discussion about positive images of aging has been going on for five or six decades. “Successful Aging“, by which we mean active, healthy and productive aging, is the buzzword that was used in the gerontological and, later on, political debate. The idea was to overcome the traditional, deficit-oriented images of aging. But ultimately this has led to a new problem, namely that we now have one-sided, positive images of aging that can put us under tremendous pressure. Illness and fragility are perceived as personal failures and a deviation from the standard of the fit and active “silver ager”.

"If we were made of stone, we would not need morality." (Mark Schweda)

So one-sided concepts of aging are not a solution?

Schweda: The concept of “Successful Aging“, which originated in the U.S., reflects social values that have not been properly considered, and that’s a problem. The need for critical reflection here is one finding of our research project. We need more nuanced images of old age. We must take into account that aging is a process of individualisation, that the older generation is heterogeneous, and a single standard image of old age can’t do this. Aging is an ambivalent process with both positive and negative aspects that can have very different outcomes both at the individual and societal level.

Zieschang: All over the world, social structures and attitudes towards aging are changing. It is important not to create pressure by making rules for how everyone should age. What “aging well“ means is determined individually and on the basis of one’s own history. For patients born in the 1920s, having attained a certain level of security is often sufficient – a roof over one’s head, having enough to eat, being well cared for and surrounded by cherished mementos and the know-ledge that one’s children have made something of themselves. Those born in the 1930s, and certainly those born in the 1940s, are generally less easily satisfied.

Schweda: Ultimately, old age holds up a mirror to society. The baby boomer generation, for whom the ideals of self-realisation, staying active and youthfulness are key to a good life, is now reaching the retirement age. This is likely to have a lasting impact on our perception of aging. However, we may well see a clash when these ideals come up against the inescapable realities of aging. I’m curious to see what happens. In the research project mentioned above, we also worked empirically and asked people who are getting older – it affects us all – what they consider to be a good, successful life in old age. We observed that people’s ideas on the subject vary greatly, and that while good health is certainly considered important, it by no means plays a dominant role – aspects such as participation, education and staying active are in the foreground. We must therefore ask people what they actually think, and not just rely on models formulated by experts.

Professor Zieschang, you mentioned the importance of social resources – but in the coronavirus pandemic social contacts have been considerably reduced. What do you think about the restrictions for residents of care homes, for example?

Zieschang: That’s a controversial issue since these people can’t make the decision themselves, but are subject to rules made by the care home management and politicians. For older people living at home, weighing up the pros and cons hasn’t been and isn’t easy either. We are currently examining the impact of the restrictions in a research project conducted with people aged 60 and upwards. In care homes, as in rehabilitation centres and hospitals, extremely restrictive measures were simply put in place without any consultation. Patients perhaps had the option of refusing rehabilitation measures under these conditions, or breaking off this or that treatment – but people in care homes have no other home. Yet they weren’t adequately and regularly involved in the discussion. I find this problematic, particularly because when it comes to rolling out a vaccination programme, we’re talking about a period of time that may well extend beyond the lifetime of many care home residents. For some of them this means restrictions for the rest of their life.

How do you see this from an ethical perspective?

Schweda: In an uncertain situation, it was right to take a cautious approach and put comprehensive protective measures in place. But now we have a better idea of the risks, and it is our duty to examine what measures are really necessary and effective. We must find creative solutions, for example for care homes. This means constantly balancing measures to contain the spread of the virus with fundamental rights and freedoms, quality of life and health.

Zieschang: I think it’s good that in Germany a clear decision was made from the outset: we will protect vulnerable groups, including older people, and we are prepared to pay a high social and economic price for this. It is a considerable sacrifice on the part of the community, which I also see as strong protection for us health care providers. We have yet to see the after-effects in countries like Italy, France and Spain that were struck hard in the first phase of the pandemic – perhaps in the form of post-traumatic stress disorders or in the form of emotional blunting in increasingly streamlined healthcare systems. All these effects will also need to be evaluated in the future.

The term “vulnerability“ was just mentioned. This is something you investigated in a research project. You examined the question of our moral obligations vis-à-vis the vulnerability of the older generation. Did you come up with an answer?

Schweda: In moral philosophy there are schools of thought according to which vulnerability is ultimately the root of all morality. If we as human beings were not vulnerable, if we were made of stone, we would not need morality. Morality has to do with consideration for others, with sensitivity for each individual’s need for protection and help. In this respect, vulnerability is a fundamental characteristic of all human beings. And then there are particularly vulnerable groups, such as those we focus on in research ethics: Do pregnant women need special protection in medical studies? What about children or the elderly, or people with cognitive impairments such as dementia? We have an obligation to take special protective measures with regard to people whose interests are particularly at risk.

You just mentioned a vulnerable group, dementia patients, which you are both researching – potentially working together in the future. What is your focus here?

Zieschang: The risk of developing dementia has decreased in recent decades. However, due to the increasing older population, the absolute numbers are rising. Since nowadays hospitals perform as many operations as possible as outpatient procedures, the proportion of particularly vulnerable and older patients in hospitals is growing: today, 40 percent of acute care patients aged 65 and over have cognitive impairment. I have been studying the special requirements of this group of patients ever since I started working in healthcare research. As a young doctor I helped set up a special ward for dementia patients at the Bethanien Hospital in Heidelberg. This project was the first of its kind to be published in Germany.

"Many dementia patients nonetheless retain an emotional memory." (Tania Zieschang)

You recently launched a research project in which, although you have not set up a new special ward in Oldenburg, you are creating a new system in this branch of care. Have you gained any new insights yet?

Zieschang: In our project we have so-called key carers – “Bezugspflegekräfte“ in German – who don’t work in shifts and who are only responsible for dementia patients. These patients seem to benefit greatly from this system. In addition, we evaluate how this impacts the rest of the care team on the ward. Although the extra staff on the ward cares for “difficult“ patients, this also requires additional organisation, and it’s important to make sure that there is someone who feels responsible for the patient at all hours of the day. The fact that these key carers have more flexible working hours and can focus more intensively on caring for their patients can also provoke feelings of envy.

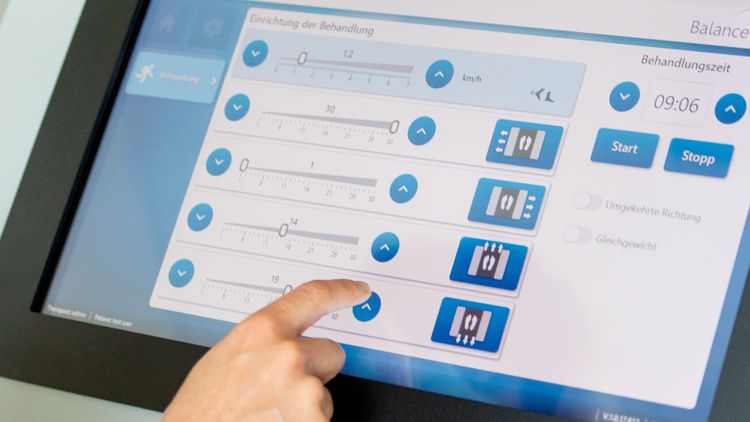

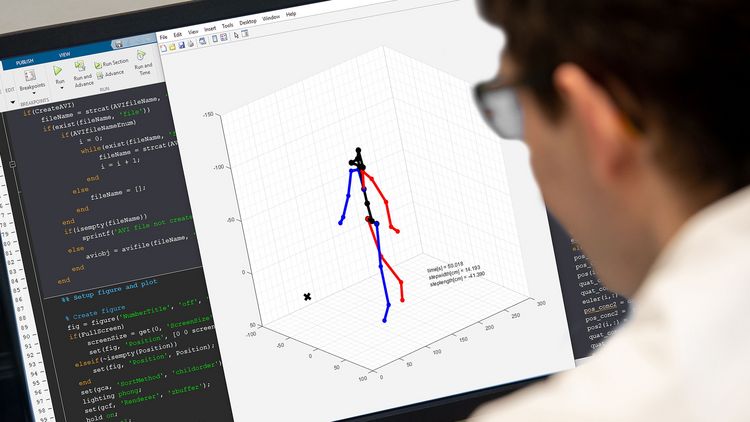

Are assistive technology systems an alternative in care, Professor Schweda?

Schweda: Smart technologies that assist with care are a growing trend. They are finding their way into the care of older people in general, and the care of people with dementia in particular. This raises a number of ethical questions about the quality of care, questions such as: What impact does interacting with monitoring systems or, for instance, a social robot actually have on a patient? Particularly if I am cognitively impaired, I may not even be able to understand what is happening. We currently have a project in which we are looking at the effects on patients and their relatives, particularly from the point of view of privacy.

You also plan to talk to this group of potential users of such technologies. Have you started the empirical work?

Schweda: Not yet, due to the pandemic. But my research also contains theoretical components – it’s about formulating perspectives, categories and ethical principles, and applying them to a specific problem. And what is already clear is that although privacy is a major topic in the debate about ethics, when it comes to constantly monitoring and controlling certain vital functions, physiological parameters or daily activities in care, in cases of dementia this category seems to fade into the background. There is very little research in this area that deals systematically with the privacy of dementia patients in general, or with their privacy in the context of assistive technologies in particular.

So these patients supposedly don’t need privacy?

Schweda: That appears to be a widespread view. Our project, on the other hand, starts from the premise that people with dementia absolutely need privacy, and that we perhaps need to review our understanding of this concept in order to adequately reflect this – even if the individuals in question perhaps no longer realise that their privacy is being violated.

Zieschang: Or forget it immediately.

Schweda: So perhaps we need to revise how we think about privacy. We must consider what it really means for us all to have a private sphere, beyond the protection of personal data. Particularly when it comes to home care, where there is very intimate contact between patient and carer in a familiar environment, something changes when technologies suddenly come into play. This is what we want to explore in our interviews.

Zieschang: What many people probably don’t realise is that many patients with impaired short-term memory nonetheless retain an emotional memory of situations. That means that although they may no longer be able to remember an encounter on a cognitive level, certain emotions remain imprinted – whether I felt comfortable or, whether instead I felt misunderstood. Each positive interaction can help patients, also in the long term.

The emotional dimension remains.

Schweda: And that is a perfect example of what studying dementia can do for us: it reveals certain dimensions of human existence that we often ignore. The American bioethicist Stephen Post says that we live in a “hypercognitive society“ that places inordinate emphasis on people’s powers of rational thinking and memory. This means that many other aspects are disregarded: embodiment, emotionality and affectivity. In the process of studying dementia, I personally am learning that we also need to think about ethical questions in a new way.

Zieschang: I have encountered many families in which a case of dementia has added an entirely new emotional depth to the relationships with the patient. This is particularly evident with men born in the 1920s who may have shown very little emotion over the course of their lives, but when suddenly all the cognitive abilities start to fall away, an inner core is revealed. Some families emerge stronger from this experience, with the feeling that they have at last come to know this person properly.

Schweda: Unfortunately, as a society we propagate an image of dementia as the worst thing that could happen. According to this logic some people would prefer to die rather than live with dementia. We need to work on this. We don’t want to trivialise dementia and the dramatic changes that accompany it, but this exaggerated doom-mongering that results from a one-dimensional self-image that is also narcissistic …

Zieschang: For example when celebrities choose to commit suicide after a dementia diagnosis, there appears to be so much vanity in that decision – they can’t bear the idea of the façade crumbling.

The loss of control.

Zieschang: Precisely.

Schweda: What we can learn from reflecting on aging and old age in general is to accept that our possibilities and capacities are limited. And to not narcissistically perceive our mortality and limitations as an insult, but to recognise these things as part of our human existence.

Zieschang: And also recognise that we can’t determine how our lives end. At some point we have to let go.

Interview: Deike Stolz

This interview was first published in the current issue of the research magazine EINBLICKE.