More

Contact

Thousand-year-old sediments from the Atlantic Ocean show how biodiversity in the oceans could develop with climate change. A team from Bremen and Oldenburg is conducting joint research - also to better assess how to protect marine life.

The marine environment will change with climate change. That much is certain. Some parts of the ocean will warm faster than others, and ocean currents will change. For several years now, researchers have observed that algae and animals from the southern latitudes of the Atlantic are moving into the North Sea because it is also getting warmer. However, the extent to which climate change will change the biology of the oceans is difficult to estimate today. No one can look into the future and predict what species communities will look like in 100 or even 500 years' time.

However, to get an idea of how human-induced climate change might affect the future, geologists and biologists from the Universities of Bremen and Oldenburg are looking to the past - to the period after the last Ice Age, when the climate changed very rapidly: around 18,000 years ago, the average global temperature began to rise rapidly. Within 7,000 years, the average temperature had risen by five degrees - a huge jump.

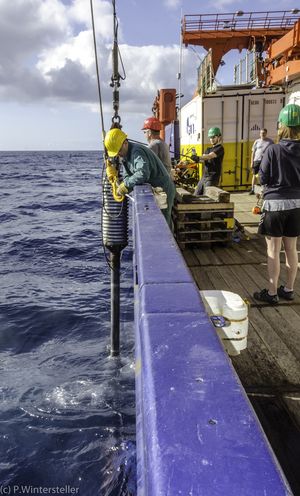

"We studied how the species communities of plankton organisms in the Atlantic changed at that time - in order to learn from this for the future," says Tonke Strack from the MARUM- Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen. Strack is a geoscientist specialising in the analysis of sediment cores from the sea floor. Such cores contain the deposits of organisms that have sunk to the seafloor after death - such as the shells of plankton, often organisms only a few thousandths to a millimetre in size.

They contain information about when and in what quantities certain plankton species were found in different regions of the ocean. Strack has studied three groups of tiny marine organisms - coccolithophores, dinoflagellates and planktonic foraminifera; all unicellular organisms that form hard shells that accumulate in the sediment.

The results show that the species composition of the plankton changed significantly as temperatures rose between 18,000 and 9,000 years ago. In particular, there was a clear northward trend. As water temperatures rose, many more southern species migrated to temperate latitudes. In turn, some temperate species spread further north. Overall, the number of species increased, especially in the mid-latitudes.

One detail is particularly interesting: although the average global temperature barely increased for about 9000 years, species communities continued to change. The global warming of that time continued for another 4000 years or so. Only then did the range of species slowly stabilise and change very little. "We see this effect above all in the dinoflagellates and foraminifera," says Strack.

To cover the ecological dimension of this work, Strack worked closely with researchers from the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment at the University of Oldenburg as part of the Cluster of Excellence "The Ocean Floor - Earth's Uncharted Interface". "The collaboration has been absolutely fruitful," says Oldenburg evolutionary biologist Dr Marina Costa Rillo.

"We want to understand the extent to which the marine environment and biodiversity are changing as a result of climate change. And somehow we have to estimate how much this change is. But we have very little long-term data. This is because, until a few decades ago, researchers hardly ever systematically recorded the number of marine organisms in different regions. As a result, there is no baseline against which researchers can assess and evaluate the current changes in the oceans.

"Tonke's data give us a picture of how species communities can change over time as a result of climate change. They also show that these changes may be different than expected," says Rillo. For example, we would have expected that the communities of dinoflagellates and foraminifera would not change if the strong global warming stopped, as it did 9,000 years ago.

For organisms that have adapted to warm conditions, it is now getting even warmer - and much faster than after the last glaciation.

For Strack, on the other hand, working with Rillo has been beneficial because she looks at the geological information from the sediment cores from an ecological perspective. "You can measure biodiversity in the sea in many different ways. You can look at whether the individuals of a species are increasing, or you can just measure the number of species," says Rillo. "So you have to have a very clear idea of what you want to measure."

To measure the impact of climate and ecological change, the team from Bremen and Oldenburg decided to measure the frequency distribution of species - in other words, the percentage of individual species in different areas of the Atlantic.

Of course, Tonke Strack and Marina Costa Rillo cannot predict how the marine communities will develop in the future. But it is clear that the effects of climate change may be more complex than expected. "In addition to the warming of the last 24,000 years, human-induced climate change is now causing further warming," says Strack.

"For organisms that have adapted to warm conditions, it is now getting even warmer - and much faster than after the last glaciation". Back then, the temperature rise took over 7,000 years. Now, if things go badly, it could be another four to five degrees higher in just a few hundred years.

Strack and Rillo plan to continue their collaboration in the future, and their project results will be included in the application for the joint cluster of excellence of the Universities of Oldenburg and Bremen. The researchers are also interested in how biodiversity in the oceans can be better protected. The interdisciplinary cooperation between the two universities is particularly important for this, says Strack. "Among other things, we want to find out how we can use information from the past to support current conservation policy and thus better manage the effects of human-induced climate change.”

This text has been translated from German with the help of KI.