A research group at the University Medicine Oldenburg has developed a new AI model called CarbaDetector that is better at identifying bacteria that are resistant to reserve antibiotics (also known as “last-resort” antibiotics) compared to other methods currently in use. In a study published in the renowned scientific journal Nature Communications, the team, led by Axel Hamprecht, Director of Institute of Medical Microbiology and Virology, demonstrates that the new CarbaDetector machine learning model, which is available for free as an open-access web-app, delivers fewer false positives than other testing methods currently in use in laboratories and outperforms standard screening algorithms.

“Standard screening methods often produce false positive results which lead to further tests that cost both time and money and are basically unnecessary,” explains Dr Linea Katharina Muhsal, first author of the study.

The Oldenburg AI was designed to accurately identify bacteria that produce enzymes that inactivate several antibiotics. These enzymes, called carbapenemases, destroy carbapenems, a class of “reserve antibiotics” which doctors only use as a last resort for treating cases in which bacteria have developed resistance to regular antibiotics. The restricted use of these antibiotics is intended to prevent the development of further resistance. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE), which the CarbaDetector is able to detect, can cause various diseases, including urinary tract infections, sepsis and pneumonia. These bacteria are particularly hard to combat because as well as being resistant to many standard antibiotics they are often also resistant to reserve antibiotics. According to the World Health Organisation, at least 30,000 of the more than half a million people who die each year as a result of antibiotic resistance have diseases caused by CPE.

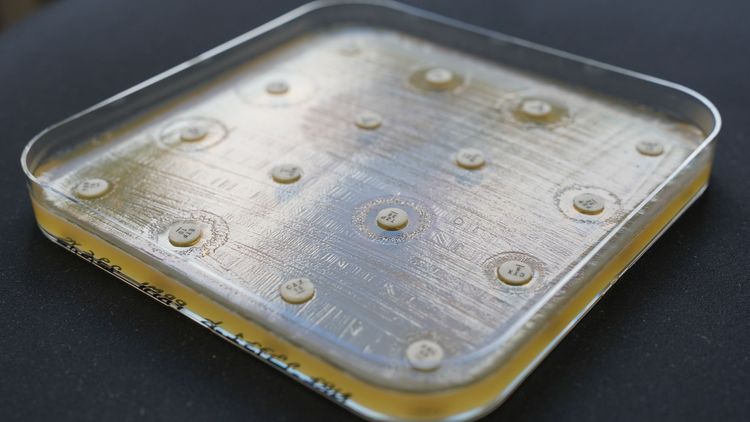

Similar to other screening methods, CarbaDetector analyses how bacterial isolates react to various antibiotics in the lab. The key factor here is the diameter of the circles that form when laboratory staff place discs impregnated with antibiotics on the bacterial culture. These diameters, known as inhibition zones, occur because the antibiotic being tested inhibits the growth of bacteria in these zones. Various committees, including the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), have developed algorithms that use these diameters to determine whether the tested bacterium is a CPE. Such algorithms detect positive samples with a high degree of accuracy – but they often misclassify negative samples as positive ones, leading to false positive results.

To test the functionality of their AI model, Muhsal, Hamprecht and their team of researchers compared CarbaDetector’s performance with that of two standard algorithms already widely used for antibiotics resistance testing, the EUCAST algorithm and another standard algorithm developed by the French Society for Microbiology. Two datasets comprising a total of 800 bacterial isolates were analysed using CarbaDetector and the two standard algorithms. The researchers found that CarbaDetector was just as effective as the two standard algorithms at detecting positive samples, while producing a significantly lower percentage of false positives. It erroneously marked only around 13 percent of the negative samples as positive, whereas that figure rose to between 27.8 and 61 percent for the standard algorithms, depending on dataset and algorithm.

CarbaDetector is freely available for research purposes. “We want to develop the model and continue to make it available for free so that it can be used by laboratories with fewer resources in other countries," says Hamprecht. Anyone interested can find the app at: uol.de/carba-detector.