Clara Willmann has uncovered a piece of local emigrant history. In her bachelor thesis, the student explores what centuries-old letters reveal about family connections.

The cardboard box was small and inconspicuous. It stood on a shelf in the library of the University of California, Berkeley, from 1985 until a few months ago, its only adornment the words “Emigrant letters” written on the outside. There were no further clues as to its contents.

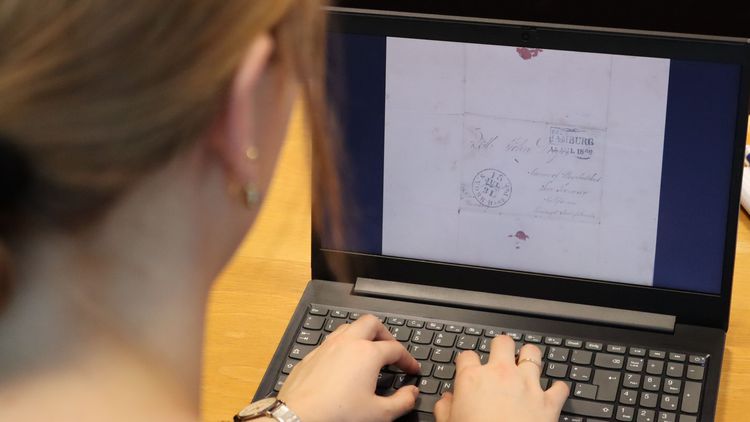

For Clara Willmann, it was an exciting moment when she received the scans of the letters that had been stored in that unremarkable box. At that point she had no clue about their contents. All she knew was that they originated from the region around the German port city of Cuxhaven and had been sent to America long ago. Now, as part of her bachelor thesis, she would be the first to uncover the letters’ secrets – including who wrote them, to whom they were addressed and what these people thought and felt. She spent five months analysing the correspondence with a view to untangling the familial relationships. “I looked at how families tried to stay in touch, strengthen their bonds and remain a family through letters,” explains Willmann, who is doing a teaching degree in history and English. The random collection of letters from the cardboard box served as the basis for her paper. The letters date back to the period from 1860 to 1872, but it was only this year that the box found its way to the German Historical Institute (DHI) in Washington DC. Dr Lucas Haasis, a lecturer at the University of Oldenburg’s Institute of History and supervisor of Willmann’s thesis, asked the DHI to send letters that Willmann could work with – which is how the digital copies came to Oldenburg. Participants in the DHI’s “Migrant Connections” project are gathering 19th and 20th century correspondence between German emigrants and those they left behind, digitizing it and making the letters, including their transcriptions, available to the general public. Willmann’s research is pioneering in this area as well. She already presented her initial findings to an international audience at a DHI roundtable in March 2021.

Handwriting and lost passenger lists

There are still large gaps in migration and emigration research today, also because it is only in the last thirty years that have letters have become a focus of academic research. "Before that, they were treated more like props from which to take quotes. Using them as a research object in their own right is still a relatively new approach," Willmann explains. The correspondence from the box consists almost exclusively of letters addressed to John Dreyer and Anna Döscher, a married couple who lived in the San Francisco area of California. There are no reply letters from the couple to those who sent them back in the homeland. This presented Willmann with a unique opportunity for her bachelor thesis. "Many studies deal with letters from emigrants and with two-way correspondence, but very few studies have focused exclusively on letters from the old homeland to people who emigrated," the student explains.

Since no one had ever worked with the letters, Willmann’s first task was to transcribe them. She read 28 letters in total, deciphering the handwriting – some of which was barely readable – and transcribing all the texts. The letters were written in Kurrent script, an old form of German-language handwriting that was used up to the beginning of the 20th century. "It helped that I could already read this old script," says the 24-year-old. The fact that the letters contained hardly any crossed-out passages also made her task easier. "People thought more carefully about what they wrote back then," says Willmann.

As her work progressed, Willmann discovered that only half of the letters were actually written in Germany. The other half were written in the US, by friends or members of the Döscher and Dreyer families who had also emigrated to America. "Once I had transcribed the letters, I was faced with the problem of not being able to match the names to the people. That took a lot of research," says Willmann. Initially, the only clear link between the letters was their addressee, so Willmann began to integrate other sources into her work. She went through church records, local archives and documents at the German Emigration Centre Bremerhaven, hoping to learn more about the lives of the two families. Through this research, and with the help of local historians, Willmann was eventually even able to create family trees for both families. The biggest obstacle to her work was that the 19th century emigrants’ passenger lists had been destroyed and were therefore no longer available as sources.

Keeping family history alive

Willmann’s painstaking detective work paid off in the end. It became clear, she says, that by writing letters people were trying to replace the lack of personal contact. The amount of effort put into keeping a relationship alive through letters seemed to correlate to the perceived sense of separation. The greater this separation was perceived to be, the more emotional the texts. The actual physical distance was less decisive: “Family members who lived close to each other but didn’t see each other on a regular basis also no longer felt as closely connected to each other,” Willmann explains.

One element of the letters which the student found particularly moving were the descriptions of bereavement. “I was touched by how these people all grieved in their own different ways, and how this genuine grief was palpable in the letters, even to me. These emotions are timeless.” For several months she followed the ups and downs in the lives of the Döschers and the Dreyers. She learned how some family members got married or died, while the fates of others remained unknown. "For me, it is a gift that the history of these people has not been lost, and that I had the opportunity to immerse myself in this world of the past."