Would people be more honest about paying their taxes if they had to publish their income? Johannes Lorenz, an economist at the University of Oldenburg, and two colleagues decided to investigate. One key finding of their research was that maximum transparency doesn’t necessarily translate into maximum tax revenues.

To many people in Germany, the idea of their tax data being made public may seem unusual. But for Johannes Lorenz, Junior Professor in Business Taxation at the Department of Business Administration, Economics and Law, it raises interesting research questions, for example: “Could such a level of transparency actually encourage taxpayers to illegally evade or legally avoid their taxes?”. His reasoning here is that if someone sees that their acquaintances are not being honest in their tax returns, the behaviour might rub off on them.

Tax evasion is a major problem for both state and society. In 2019, a report by the University of London estimated that in Germany alone, tax revenue losses amount to more than 125 billion euros per year. This then creates a hole in the state budget when it comes to financing projects in key areas such as education, research and infrastructure. Lorenz now plans to examine the phenomenon in greater detail. In previous studies he looked at how social narratives affect tax avoidance behaviour and the “race” between tax legislation and tax avoidance. Lorenz is a Research Fellow in the Collaborative Research Centre Accounting for Transparency, which is coordinated by the University of Paderborn and investigates the effects of tax and transparency regulations on the economy and society. “I’m interested in how taxation affects entrepreneurial decisions and, in particular, how income tax transparency influences tax compliance and tax revenues,” says Lorenz.

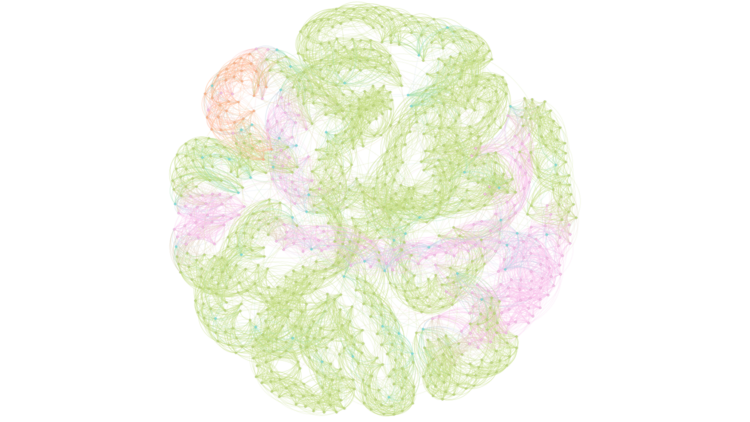

To explore these questions in greater depth, Lorenz and two colleagues from the University of Passau used what is known as a “small world” network model in which people are represented as nodes that influence each other. These computer-based models are used in economics to uncover structural relationships through simulation games based on a relatively limited number of premises.

The model designed by the three researchers simulates a fictitious neighbourhood with a population of 1,000 individuals who observe each other’s behaviour over a period of 40 years. The simulation is based on three premises: first, that neighbours can determine the real income of an individual based on factors such as the size of their house or the make of their car. Second, there is a five percent chance that the tax authority will audit a taxpayer in any given year. If someone is caught faking donations or cheating on their commuter allowance, for example, they have to pay a fine and are forced to be honest for the next four years. Finally, taxpayers are free to optimise their tax burden through legal means, which gives them the same financial advantage as tax evasion but is more complicated.

Does income tax transparency influence tax morale?

The researchers tested three scenarios: in the first, which resembles today’s situation in Germany, no one has to publicly disclose their tax data. In the second, taxable income is made public by the tax authority. This is similar to the legal situation in Norway and Sweden. In the third, there is maximum transparency: gross income, tax returns and taxable income data are all disclosed. The scientists assume that taxpayers, as rational subjects, not only want to pay as little tax as possible, but also want to gain some “social advantage”. Here the scientists are referring to people’s tendency to behave similarly to those around them. “Let’s say I see that my self-employed neighbour can afford a big house even though he has a low income according to the disclosed data. I don't want to be the fool who pays more, so I try to minimise my tax payments too,” Lorenz explains. This hypothesis is based on empirical studies that show that group pressure is a strong factor in tax evasion.

The key finding of the simulation is that partial rather than full transparency generates the highest tax revenues. In the first scenario, the people have no idea how their neighbours are behaving; tax fraud is a popular strategy here because evasion often goes undetected. In the second scenario, taxpayers can tell if their neighbours are paying less tax than might be expected, but not whether they are evading or optimising taxes. Consequently, neither strategy is encouraged by herd behaviour, and people tend to pay their taxes honestly. In the third scenario, which entails maximum transparency, it’s clear who is evading, who is optimising, and who is doing neither. Here, most people choose to optimise their tax payments using legal means. Tax evasion, on the other hand, is made unattractive by the deterrent effect of fraudsters getting caught.

“The study suggests that from the state’s point of view, partial disclosure is preferable, since this results in the lowest tax losses,” Lorenz summarises. However, he admits that the results vary depending on the size of the network, the likelihood of being audited and the tax rates. He therefore plans to refine the model in future studies in order to make the impact of different degrees of tax transparency more measurable. The results of the simulations are then to serve as an initial hypothesis for empirical studies. “In this way, our research can help to combat society’s problem of tax evasion.”