More

Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM)

Center for Marine Sensors (ZfMarS)

Part of the university is located directly at the Jade Bay in Wilhelmshaven: the Institute of Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM) has a location on the Schleuseninsel (lock island) near the southern beach, which has now been extended. A campus with a unique infrastructure.

The campus in Wilhelmshaven has belonged to the university since 2008. The red brick building was previously home to the Centre for Research on Shallow seas, Coastal Regions and the Marine Environment e.V. (Terramare Research Centre), founded in 1990 – an association of several marine research institutions in Lower Saxony, including the University of Oldenburg. The centre was primarily intended to provide technical-scientific services for the member institutions. In the course of a stronger orientation towards research, the Terramare was incorporated into the ICBM 14 years ago, where it was already represented by a „marine station”.

Today, around 90 employees and five ICBM working groups have their headquarters in Wilhelmshaven: the Geoecology, Plankton Ecology, Environmental Biochemistry, Marine Sensor Systems and Processes and Sensing of Marine Interfaces teams. The main building, completed in 1994, is equipped with various laboratories, workshops and seminar rooms for teaching – as well as special laboratory facilities that the respective groups need for their research. A core repository, a weather station and guest rooms – for example for researchers from abroad or students on internships – are also located on site.

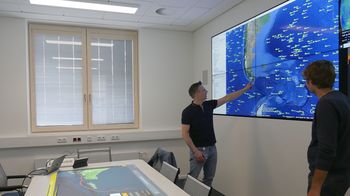

Around 600 square metres of space for research areas, laboratories, workshops, offices and a state-of-the-art mission control centre (photo): The Wilhelmshaven campus has received an extension for the Centre for Marine Sensors (ZfMarS), which was ceremonially inaugurated in May. At the ZfMarS, founded in 2017, around 20 researchers led by Prof. Dr Oliver Zielinski (pictured left) are researching, for example, how autonomous systems can be more effectively protected from the consequences of vegetation. They are also working on measuring devices designed to monitor marine plastic pollution or oil spills remotely.

The new research building offers a flexible environment for a wide variety of experimental set-ups, such as an optics lab where researchers develop sensors for the underwater world. In the control centre, the data from various research platforms – for example from the research vessel SONNE, the permanent measuring station of the Spiekeroog Coastal Observatory, the ICBM research catamaran and several measuring buoys used around the world – are brought together on large screens. These buoys drift with the ocean currents and are equipped with GPS trackers and a satellite communication module so that their data can be mapped in real time in the mission control centre.

A piece of the South Sea can be found in a container directly behind the embankment. Here, researchers from the Environmental Biochemistry group study marine communities from the Fiji Islands, Australia or Guam. 60 aquariums with a total of around 6,500 litres of artificial seawater are available for this purpose. The facility, which also includes storage and filter basins, was designed specifically for research. The team conducts experiments with corals, algae or sponges in roughly 30 hundred-litre tanks. The researchers can simulate climate change or ocean acidification in the aquariums, for example, by individually controlling the temperature and pH value of the water. In some aquariums, the environmental conditions of Guam or Australia can be realistically replicated. Not only water chemistry, but lunar cycles, day length and solar radiation can be adjusted. This is how Dr Samuel Nietzer (photo) and Matthew Jackson succeeded in reproducing stony corals for the first time in Germany in 2020. In addition, the team has various 200-litre tanks in which coral fragments and coral polyps grow for laboratory experiments. These are used to study the effect of sunscreen on coral reefs.

Between the ICBM building and the seawall you won't find a swimming pool, but a sophisticated research facility. The „Sea Surface Facility” is specifically designed to study the thin surface film that forms the boundary between the sea and the atmosphere. This highly interesting micro-layer is the special field of the research group Processes and Sensoring of Marine Interfaces.

The team uses a pump system to fill the eight-and-a-half-meter-long, two-meter-wide and one-meter-deep basin with fresh seawater from Jade Bay in order to understand the processes that take place in this layer. For experiments, precipitation and currents can be generated; to create windy conditions, the transparent sliding roof may be opened. Swivelling arms equipped with probes and sensors – some in miniature format – can measure temperature, salinity, pH and other parameters at different water depths. To sample the 0.05 millimetre thick surface film directly, the researchers skim the layer off the surface. To do this, they dip glass panes into the water and carefully pull them up again. Due to the surface tension, the film sticks to the pane, can be removed with a shower cleaner and then examined in the laboratory.

Twelve cylindrical barrels lined with black insulating material, large enough to hold 600 liters of water each, stand tightly packed in a shed behind the main building. They are called planktotrons, and it is in these containers that the Plankton Ecology working group conducts their experiments. "We use them to study natural plankton communities under controlled conditions,” reports biologist Dr Maren Striebel (photo).

The containers are so large that countless microscopic algae, bacteria and crustaceans live together in them almost like in natural waters. The researchers can vary the amount of nutrients and light conditions, imitate high and low tides or storms and set three temperature zones. In this way, seas and lakes, salt and fresh water, future and past climate can be simulated.

Recently, the team filled the planktotrons with North Sea water from a site off Helgoland. In other experiments, the researchers set temperatures between two and six degrees Celsius to study communities of Antarctic phytoplankton. The systems run largely automatically.