Linguist Hans Beelen has linguistically analysed the notes in the journal of a Dutch group of researchers who spent a winter in the Svalbard archipelago in the late 1960s – and found many peculiarities. Last summer, he followed in the tracks of the expedition.

Boot Valley, Mammoth Glacier and Xanthoria Rock, also called Red Rock – these landmarks on the island of Edgeøya are very familiar to Ko de Korte. The Dutch biologist and Arctic expert explored them more than 50 years ago, when as a student he and three other young Dutchmen spent the months from September 1968 to August 1969 on the island – the third-largest in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean.

This summer, de Korte, who is now almost 80 years old, revisited the island on an Arctic expedition organised by the University of Groningen. He was accompanied by Dr Hans Beelen from the University of Oldenburg's Institute of Dutch Studies, to whom above all the names of various locations on Edgeøya were familiar. The linguist is studying the language used by the members of the 1960s expedition as they went about their isolated daily lives on the island, studying polar bears and exploring its geography.

For as was customary on expeditions to remote – from a European perspective – parts of the world, the four biologists kept a journal during their stay on the island's Kapp Lee headland. In this journal they recorded both their scientific findings and details of their everyday life, such as what food they ate, whether anyone in the group was ill, and the sites they visited on a regular basis. Names like Stövlardalen (Boot Valley) or Mammuth-gletsjer (Mammoth Glacier) appear again and again in their notes.

Imaginative neologisms

From a linguistic perspective, the journal is a boon, because the words and phrases that the four men used in their daily life and which also appear in the journal display many peculiarities. "Over time, the group developed a language all of its own," explains Beelen, who has been studying similar historical documents for years, and came across the journal of the Dutch Arctic expedition in the course of this work.

The explorers came up with a number of imaginative neologisms. To orientate themselves in the largely unchartered terrain, they thought up names for places that had none. They named Boot Valley after the manufacturer of the Swedish boots (Graninge stövlar) that they wore on their scouting expeditions. Mammoth Glacier got its Dutch name because one of the members of the expedition had dreamt that a mammoth was buried under the masses of snow. And Xanthoria Rock was named after the lichen that makes the rock glow red.

The young explorers also came up with humorous designations for things they used on a daily basis. The haardstoel (stove chair) was a whale bone that they used as a chair, which stood next to the stove. The first polar bear the researchers observed was named Barend, after a bear in a popular Dutch children's TV series. There were also various running gags. When someone said they had to go to the kerk (the Dutch word for "church"), they meant they were going to the toilet, because when they first arrived they used an octagon-shaped trapper's hut, dubbed the kerk, as a loo.

„Language is a flexible instrument”

Abbreviations, neologisms, the mixing of different languages – the small changes in the way of talking and expressing themselves that are in evidence throughout the journal are like a microcosm of what defines human language – namely the way it evolves in little steps, says Beelen. "Language is a flexible instrument, and this group language exemplifies this perfectly," he adds.

But beyond that, the language that de Korte and his colleagues created for themselves also fulfilled the critical function of helping them cope with the challenges of everyday life in the Arctic, the linguist explains. Language fosters a sense of belonging, for example. And jokes can be essential for surviving difficult situations in that they help to defuse tensions, for instance between individual members of the expedition, he adds.

All this can be deduced through careful analysis of the researchers' notes, says Beelen. In the meantime, he has compiled his scientific findings in a book. Published at the end of November 2022, Een jaar bij de ijsberen makes the historical documents of the Dutch expedition to the Arctic, as well as Beelen's linguistic analyses, accessible to everyone.

It was thanks to this year's University of Groningen expedition to the Arctic, officially titled Scientific Expedition Edgeøa Svalbard (SEES), that Beelen went beyond his mostly theoretical work and was able to see the sites on Edgeøya for himself, in the company of a member of the original expedition. "As soon as I heard that the University of Groningen was planning an expedition to Svalbard, I applied for a place," he recalls. And he got it.

Many traces of the expedition had been erased

So together with Ko de Korte, he travelled to Svalbard with the goal of finding out exactly how the place names mentioned in the journal had come about. "Ko and I have sat down together many times before, but it was wonderful to spend more time with him, to go over details and refresh almost forgotten memories in our conversations, and to finally see all the places whose names I already knew," says Beelen. He was impressed by the fascinating landscapes, but also by the great distances that were covered by the researchers during the 1960s expedition.

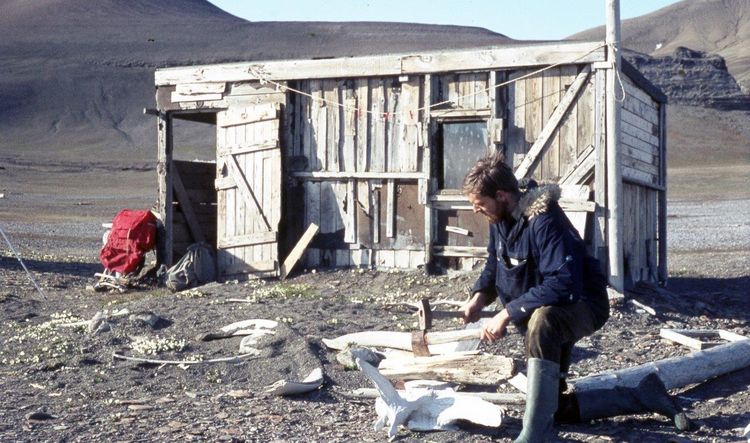

However, while on Edgeøya, Beelen also saw how many traces of the expedition had been erased over time. The building where the researchers lived had been demolished, and the glaciers had shrunk as a result of climate change. Beyond the pages of the journal, the linguistic traces of the expedition have also disappeared. When they returned from their expedition, the Dutch researchers proposed some of the place names they had invented to the Norwegian Polar Institute, but without success. Boot Valley or Xanthoria Rock are nowhere to be found on official maps of Svalbard.