The effects of climate change are increasingly tangible. Reforms at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could serve to increase its political clout and thus advance the battle against global warming, argues sustainability researcher Bernd Siebenhüner.

How important is the IPCC?

The IPCC provides a basis for science-based political decisions on climate change. It points out options for action but does not make any direct recommendations for measures by states. This has prompted some people to say that the IPCC is just a show, but I don't see it that way. The IPCC wields significant political power and has achieved many successes. It is highly visible internationally and has a special role at the interface between science and politics. It is listened to in climate talks, and also by governments, and it is a key point of reference in the scientific community. The IPCC’s reports provided a strong scientific foundation for the Paris Agreement of 2015, in which almost all the countries in the world agreed to act to keep global warming significantly below two degrees Celsius.

Nevertheless, together with an international group of researchers you recently outlined scenarios for a reform of the IPCC in an article published in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change. Why do you think reforms are necessary?

Now that the current assessment cycle has ended, the IPCC finds itself to a certain extent at a crossroads – with the opportunity to reconfigure itself for the future. This poses questions such as: What lessons have been learned in the current cycle? What can be done differently in the future? As a result of various political, scientific and ecological developments, today's environment is very different to what it was in the last decades. This was the motivation behind the article in Nature Climate Change and also for our recently published book.

What has changed?

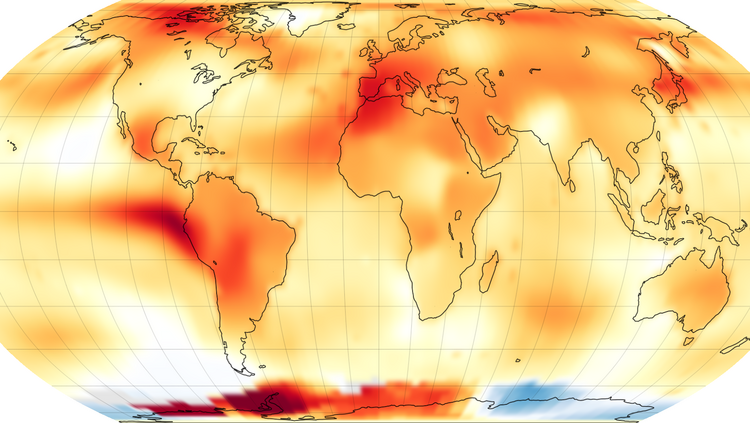

In the early days of the IPCC, the focus was very much on the questions: Does climate change actually exist? Is it caused by humans? And where is the critical threshold of climate change which must be avoided at all cost? These questions have now been answered: Yes, the climate is changing, very clearly. The point at which it becomes dangerous has also been clarified. For a long time, it was assumed that the threshold was an average global warming of two degrees Celsius. In the Paris Agreement of 2015, the signatories agreed to limit the rise in temperature to 1.5 degrees if possible, because there were indications that an increase of two degrees would already be pretty risky. The IPCC’s special report on the 1.5-degree target, which was published in 2018, confirmed how serious the situation is, and how quickly we need to act on greenhouse gas emissions to keep temperatures from rising by more than 1.5 degrees. It shows very clearly how dramatically the climate, natural landscapes and ecosystems are changing. This has significantly changed the political discourse landscape in the last five years.

What challenges do you see the IPCC facing in its work?

The IPCC is bound by its original mandate, which stipulates that its reports should be relevant to government policy without, however, prescribing those policies. And states make sure that this is adhered to. The IPCC report contains measures for climate protection, but only points out options. It does not give a breakdown of what would have to be done in Germany, for example, in order to meet the climate targets. Nor does the IPCC allocate an emissions budget to each individual country. It is therefore not allowed to give a detailed analysis of the measures that need to be taken by each of the actors in the key category of actors, the nation states, which after all lead the global climate negotiations. This restricts its impact on national policy. The reports are in effect nothing more than a menu: governments are free to pick and choose what they take from them.

Why is this problematic?

If we want to avert the biggest dangers of climate change, we need to act very fast. The IPCC needs to be able to specify measures for individual countries, because the logic of the Paris Agreement is different from that of the preceding Kyoto Protocol, which set binding global emissions limits. The Paris Agreement has given nation states more leeway and left them more or less free to decide for themselves by how much they want to cut their emissions, and how to achieve their own targets. Ideally, these Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) were to add up and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. At the time of the Paris Agreement, however, taken together there were only enough NDCs to limit global warming to around 3.5 degrees Celsius. Today that figure stands at around 2.6 degrees Celsius. But we should bear in mind that these are only declarations of commitment for now. We can see in Germany, as in other countries, that these targets are often not met. It is a shortcoming of the agreement that the pressure it exerts at the international level to make countries formulate and implement ambitious targets remains relatively weak.

There are further points of criticism regarding the IPCC, for example that the social sciences should be more involved.

Exactly. Up to the 2000s, climate research on the whole was very science-oriented. In the meantime, however, the climate debate has become far more sociopolitical in orientation. The question now is: how can we curb climate change, what do we need to do differently? The third part of the Assessment Report, which deals with climate protection, has also been dominated by economic considerations so far.

What do you see as the IPCC’s task now?

The perspective needs to be broadened. Problems regarding social development are already being taken into consideration in the climate discourse; climate justice is a buzzword. But problems such as overuse of resources haven’t received much attention so far: if we invest massively in renewables and electric cars, this involves extracting a lot of resources and high energy consumption. The planet’s resources are not infinite, so there’s a risk that problems will simply be shifted rather than resolved. We know all too well from observing environmental policy how one problem is solved, but another created in the process. We need to avoid this. A lot can be achieved without using new resources or energy-intensive technology, simply through changes in behaviour or policy changes, for instance.

What concrete scenarios do you see for the future of the IPCC?

The first is what we called “business as usual”: the IPCC carries on as before, which could be translated as resting on its laurels, perhaps becoming less and less relevant and heeded. To put it bluntly, the IPCC threatens to sink into insignificance if it chooses this path.

What about the other scenarios?

The second scenario calls for a greater diversity of perspectives: the IPCC could open up to actors other than nation states. This would include state actors at other levels, for example. Local governments or regions in states where climate protection is not at the top of the agenda can also make a difference. Under the Trump administration, the individual states of the US were comparatively active – California, the states of the New England region, even Texas. Civil society also plays an important role, of course. Fridays for Future and other such organisations. They want to have a say, ask questions and work on solutions. Companies also have huge scope for action and increasingly want to get involved. They are an important social actor and also potential recipients of recommendations.

And the third scenario…

... would be for the IPCC to provide greater impetus for political change. However, for the IPCC to wield more political clout, major institutional reforms would be necessary.

Are there also examples of how environmental reports can have a stronger political impact?

As a highly regarded organisation, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been publishing environmental assessment reports for 30 years. These reports provide member states with sometimes very critical feedback on how, for example, their chemicals policy or energy policy need to be improved. It is my hope that countries will increasingly come to accept the IPCC’s recommendations, too. This could set in motion reforms which could then have an impact in the next assessment cycle, and also on climate policy.

Thank you very much!

Interview: Ute Kehse