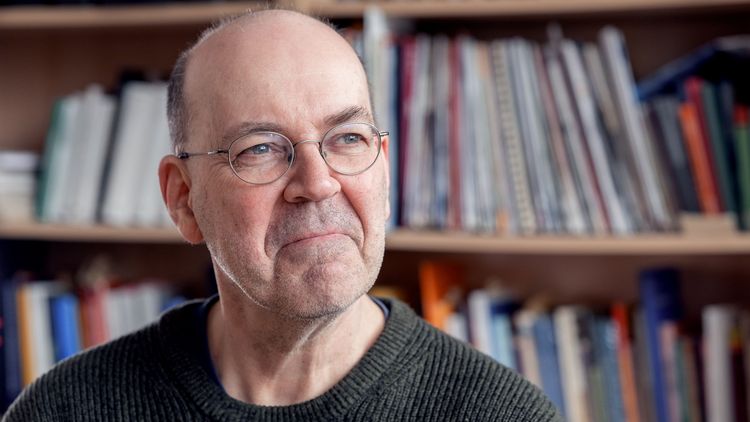

On January 27, people around the world commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. In this interview, history educationalist Dietmar von Reeken talks about the problematic aspects of ritualised remembrance – and the alternatives.

Since 1996, Germany has commemorated the victims of National Socialism every year on January 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by the Red Army. In 2005, on the 60th anniversary of the liberation, the United Nations designated January 27 as “International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust”. Why was this day of remembrance introduced?

International Holocaust Remembrance Day emerged from the Stockholm process which began at the end of the 1990s. Founded in Stockholm, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance drew attention to the fact that the number of living witnesses to the Holocaust was diminishing. The aim of the day of remembrance is to keep the memory of the victims of the Holocaust alive and to make people realise how important the fight against antisemitism and racism still is. Holocaust Remembrance Day helps German society, and the German state in particular, to structure and ritualise remembrance. This is reflected in acts such as the Bundestag holding an hour of remembrance or flags being flown at half-mast. At the same time, both the internationalisation and ritualisation of this remembrance are to a certain extent problematic.

Why?

Take the internationalisation: the “globalisation of the remembrance” is not entirely uncontroversial in academic circles, because the Holocaust was initially a specific historical event in Germany and, emanating from Germany, in Europe. With a global day of remembrance, however, the Holocaust sometimes seems to be just a synonym for radical tyranny and its consequences rather than a concrete historical event. But if the Holocaust also stands for other mass crimes and not just for the singular historical event, this is problematic, especially from the perspective of Holocaust survivors and their descendants, because their perspective may fade into the background as a result.

And the ritualisation?

As meaningful as, for instance, the hour of remembrance in the Bundestag may be, the question is: how do people perceive it, especially younger people? For example, memorial sites for the victims of National Socialism have realised that ritualised commemoration doesn’t go down well with younger visitors. This form of remembrance is too far removed from young people’s daily lives – if they’re aware of it at all, it’s through the media. But it makes little impact on them. We should therefore go beyond this and find new forms of remembrance.

So how can we keep the memory of the Holocaust alive – especially given that soon there will be no more Holocaust survivors who can tell their stories?

Many people are indeed particularly moved when Holocaust survivors, as eyewitnesses, talk about their own experiences and things that otherwise are only dealt with abstractly in school textbooks. Since the opportunities for this are becoming increasingly rare, there are for example experiments with survivors talking through holograms. Museum visitors or students can ask the hologram a question, then an algorithm determines which of the pre-recorded answers the hologram gives. On the one hand, the events may seem more vivid when witnesses of those times are digitally projected into a room to talk about their experiences. On the other hand, this approach raises the legitimate question of whether it is appropriate and dignified to meet the victims in this way, and whether this is not a form of instrumentalisation. I, too, am sceptical about it.

What other formats exist?

There are digital initiatives like the Instagram projects “Eva.Stories” or “I am Sophie Scholl”, about which I have similar doubts. If such projects make the topic more accessible to young people who are more digitally connected, then in principle they’re a good idea. The prerequisite, of course, is that the projects are of high quality, that they’re backed up by historical and didactic expertise, and that it’s clear who is responsible for them. In my view it’s crucial that such projects strike a good balance between closeness and distance. Because even if portrayals by actors or holograms come across as authentic, we can’t travel back in time. We are not part of the past, but part of the present.

School is still the main place where young people learn about the Holocaust. How can the topic of the Holocaust be dealt with appropriately in school lessons today?

Many schools and teachers are using research and discovery formats. This includes working with biographies when direct contact with eyewitnesses is no longer possible. The biographies of people who were the same age as today’s students at the time of the events are particularly effective here. In a recently published article, I explained a method with which even primary school children can learn about the politicisation of children under National Socialism through the school system, the Hitler Youth organisation and so on. By using sources such as the memoirs of people who were still children at the time we can make this politicisation understandable. In this way, I believe we can also encourage primary school children to engage with, if not the horrors of the Holocaust, then other aspects of National Socialism.

Are there other formats?

Yes, local history-based approaches are also effective in my opinion. One good example is the remembrance walk organised by Oldenburg schools every year on 9/10 November, the anniversary of the anti-Jewish pogroms of 1938. The walk has been taking place since 1981, and Oldenburg schools have taken turns organising it since 2005. Oldenburg residents retrace the route through the city along which Oldenburg’s Jewish residents were driven in 1938, before being deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. I think the remembrance walk is a very successful format because the students deal intensively and within their own environment with the biographies of people who were persecuted back then, and find their own forms of remembrance. However, there is yet another problem here.

What problem?

Studies showed more than a decade ago that in lessons on the topic of National Socialism students basically simply learn how to talk about that period in today’s society, and then retrieve that knowledge when the situation requires it, for example in an exam. This is of course highly problematic, because we want students to form their own opinions on all other topics in history lessons, but when it comes to National Socialism it seems they tend to just memorise society’s judgments instead of making their own judgments, because they don’t engage intensively enough with the topic. Therefore, we need to move away from the sometimes abstract, structured approach to history and the perpetrator-victim dichotomy and focus more on how people behaved at the time. How did a farmer, a shop assistant or a teacher become a perpetrator? Why did so many people become complicit? What were their motives – from racism to opportunism to fear? And where and why did some people draw the line? Especially in view of certain trends in our society today, I think it’s important to examine these questions.

What can history lessons achieve?

There is the idea that teaching history can immunise students against political extremes. I’m a little sceptical about that, however. We shouldn’t overestimate the influence of history as a subject. After all, what goes on in traditional and social media, in peer groups, in families and so on can’t be counterbalanced by an hour or two of history lessons per week. But it’s also clear that in view of current developments such as growing right-wing extremism, racism and antisemitism, history as a subject, as well as the topics of National Socialism and the Holocaust, are of key relevance to the present. And history lessons can, at least in some cases, create an understanding of how dangerous certain attitudes really are.

Interview: Henning Kulbarsch