Oldenburg professor Clemens Hillenbrand has been training Iraqi teachers in inclusive education for many years. The special needs educationalist discusses the progress already made and the challenges ahead.

Mr Hillenbrand, one of the aims of your project “Qualification for Inclusive Education in Iraq” was to develop expertise in special education among Iraqi teachers and thus promote inclusion in Iraq. How important is this topic in a country impacted by violence, wars and geopolitical uncertainties?

Many people, and children in particular, suffer terrible physical and mental injuries as a result of the wars, terrorist attacks and acts of violence. On top of that many families are also burdened by the death of family members, for example. If a child grows up in a refugee camp in dreadful living conditions instead of a stable family environment, it is very likely that they will be damaged by this experience. This means that there is an enormous need for inclusive measures. But the state is often unable to give these children the help they need. Not only are they the weakest members of society, they are also its seismographs: they are the first to suffer and the first to experience adverse effects. But at least there is a consensus in Iraqi society that inclusion, the right to life and the best possible living conditions for everyone are goals worth striving for.

Do we in Germany have the same concept of “inclusion” as people in Iraq?

The German government signed the corresponding UN Convention on Inclusion in 2013, and developed an action plan for the establishment of inclusive schools. Although the Iraqi approach to the concept of inclusion is very much based on international documents and, unlike in Germany, you don’t find shelves full of literature on the subject in Iraq, there is nevertheless a relatively clear understanding of the term: inclusion means providing the best possible support for all children, but especially for disadvantaged children and children with disabilities, and if possible in every school. The German debate about abolishing special needs schools, on the other hand, plays no role in Iraq because there are hardly any schools focused on children with special needs there. Instead, discussions about inclusion focus pragmatically on the question: How can we best support all children?

How have you been able to support your Iraqi partners?

We have helped them to implement international special education and inclusion standards. For example, there is a lack of expertise and specialist staff for special education diagnostics in Iraq. We worked together to identify resources and strengths on the basis of empirical research findings, which are an important basis for all education, and also to be able to better differentiate between, and diagnose, behavioural disorders, trauma, autism, physical impairments and intellectual disabilities. We also developed teaching concepts for inclusive lessons together with our Iraqi partners.

Roughly 500 students have successfully completed their studies

What concrete progress has been made?

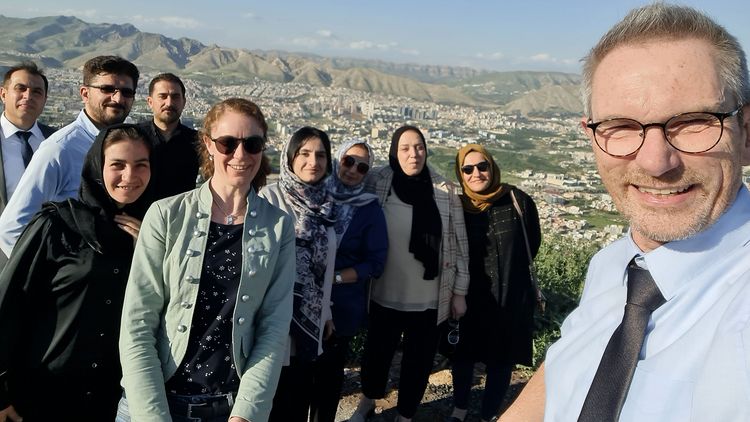

My predecessor Monika Ortmann was already involved in setting up a Bachelor’s degree programme in special education in Dohuk. I continued this work. We advised our Iraqi colleagues on programme content. In the meantime, roughly 500 students at the University of Dohuk’s Institute for Special Needs Education have successfully completed their studies. A master’s programme was also recently launched. This is quite an achievement because most teachers in Iraq only do a bachelor’s degree. Last year we visited our colleagues at the Iraqi university, some of whom we have been in dialogue with for years. We also visited local facilities for children with disabilities. Seeing the progress that has already been made with the degree programmes and training courses and learning about new structures – all this was a very special experience for me.

Your Iraqi colleagues have also visited Oldenburg several times. How important were these visits?

The visits to our local schools were particularly instructive for them because they were able to experience the possibilities of inclusion work first hand. Here in Germany the support system for people with disabilities is almost uniquely wide-ranging – from inclusive pre-schools and nurseries to all the different types of school and special education or socio-paediatric centres. It was very important for our partners to see how, in addition to children with clearly visible disabilities, those with less obvious disabilities can also be supported.

Do personal connections between Germany and Iraq also play a role?

Yes, we once entered a classroom during a school visit in Oldenburg and introduced the Iraqi delegation. Some of the schoolchildren spoke to our guests in Kurdish because they came from the same region as refugees. This was a moving experience for everyone. The Yazidi community, which is strongly represented in Oldenburg, has also supported us in many projects.

What challenges remain – for inclusion in Iraq in particular, but also for projects like the one that has just been completed?

Quite a few. Many Iraqi schools have only small classrooms in which in some cases sixty or more children are squeezed together. How are you supposed to find space for a wheelchair in such a room? So it starts with practical issues like that. And with classes of this size it’s hardly possible to teach in a differentiated way, or to give pupils detailed feedback. Then there are staffing problems. The state lacks the money to hire the necessary specialised staff, and teachers’’ salaries are so low that many are forced to take on a second job. As a result, they often don’t have time for discussions or additional training. A third problem is the lack of networks. There is no civil society organisation that campaigns for special education research and investments in inclusion. But at least we were able to initiate the establishment of such an association at our last meeting. Then there’s another problem which, unfortunately, has more to do with Germany.

In what way?

Unfortunately, many Iraqi teachers and students are unable to obtain a visa for Germany – our project partners also had difficulties. The German government could make things easier, especially since Germany has a very good reputation and is well-trusted in the countries of the Middle East. The same goes for the EU. Unfortunately, however, the EU does very little to promote education in the region, even though international cooperation on education is vital, because good education creates prospects and helps to alleviate social problems that otherwise form the basis for new conflicts.

Despite all the obstacles, how has your work in Iraq affected you personally?

Above all, it has motivated me to keep seeking dialogue and exchange. Our partners’ interest in our work has shown me how much we can give. I was also encouraged by the strong commitment to inclusion that exists there, despite living conditions that are very different to those here in Germany. I definitely want to maintain the contact with Iraq to keep the dialogue and cooperation going. I’m especially happy to know that the Iraqi teachers in training will bring their knowledge about inclusion to schools there and pass it on to others. It’s wonderful to see this and it strengthens my conviction that I can actually make a difference through my work.

Interview: Henning Kulbarsch