Learning to write below deck

Learning to write below deck

Learning to write below deck

What the Bremen sailor Johann Pohl put down on paper normally would not have been preserved in an archive. His is one of the many yet unheard voices that the digitization of the "Prize Papers" makes heard and thus adds to the knowledge about past centuries.

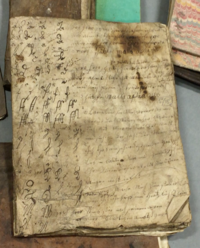

The little notebook must have meant a lot to Johann Pohl. Its tattered, weather-beaten pages attest to frequent use and exposure to the elements. It is likely that its owner, a sailor from the Hanseatic city of Bremen by the name of Johann Pohl, carried it around with him at all times. It was in Pohl's possession for four years, until it was literally snatched from him aboard the Concordia, a Bremen merchant ship captured by English privateers on 6 April 1758 off the chalk cliffs of Beachy Head in the English Channel – a notorious spot for such manoeuvres.

Although the Concordia was sailing under the neutral flag of Bremen on its way from the Caribbean to Amsterdam, it was coming from French waters. And since at that time France was at war with England, this suspicious circumstance was deemed reason enough to confiscate not only its cargo of coffee, sugar and cotton, but also the mailbags it was carrying, as well as the ship's papers and the personal belongings of the captain, the nine seamen and one boy on board that made up its crew. These documents – known as the "prize papers" – were then submitted as evidence before the High Court of Admiralty in London so that it could uncover any links to an enemy party, in this case France, and decide whether or not the capture of the ship had been legal. For centuries the capture of "enemy" ships and their cargo was considered a legitimate tactic of warfare during times of war, including an own jurisdiction.

Although Johann Pohl's notebook was not used as evidence in the ensuing court process, it was kept with all the other documents and items taken from the Concordia in the archives of the High Court of Admiralty, and stored for several decades in the Tower of London together with the papers and artefacts seized from more than 35,000 other ships the English captured between 1652 and 1815. During that period alone, the European powers fought out 14 naval wars in their own waters and on the world's oceans. In 1858 the entire collection comprising several million historical records and objects of many different types and origins was moved to The National Archives (TNA) in Kew, London. Sitting in the archives, the papers and items were all but forgotten for many years.

In the Prize Papers Project, which officially began in 2018, based at the University of Oldenburg and the UK National Archives London and funded within the Academies Programme of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities, experts are cataloguing and digitizing the entire Prize Papers collection. The aim of the project is to make the records available to the scientific community and the general public in an open access database, while at the same time conserving the collection in London in its original condition as far as possible. The project is jointly funded by the German government and the federal state of Lower Saxony and is set to run until 2037. Alone the 90 different document types that make up the collection continue to offer new surprises and insights, inspiring historical research in Oldenburg and across the globe. For Oldenburg historian Dr. Lucas Haasis, the notebook belonging to Johann Pohl – or "Jean Pol" as the ship's crew called him – is among the most moving documents he has encountered so far.

"At first glance it looks like a scruffy notebook used for writing exercises," says Haasis, who coordinates the international research cooperations connected with the project. "But on closer inspection, you see that it is much more. For one thing, it shows very clearly that more people were literate or learning to write in the 18th century than has long been assumed – and not just men from bourgeois or aristocratic circles. We find a lot of letters from women and from people from different social classes in the Prize Papers; children wrote letters, and sailors, too. We wouldn't have expected anything on this sort of scale." Since writing skills were not required for seafarers from lower ranks at that time, historians had long assumed that most were barely able to sign their own name. However, the crew of the Concordia presents a far more nuanced picture.

The notebook also bears witness to exactly how this man, who was at sea for years, taught himself to write or had others teach him: first he practiced writing individual letters, then monotonous sequences of letters, and finally certain passages of the Lord's Prayer, repeating them over and over again in his notebook.

"The practice of learning to write, normally taking place in grammar schools, had made its way on deck – or rather below the deck – of the Concordia," Haasis observes. The traces of wax on the pages of the notebook suggest that Pohl practiced his writing with great assiduousness, working even by candlelight.

Why he went to all this trouble is revealed on the last page of the inconspicuous booklet, which contains a little poem he penned for the christening of his baby daughter:

As a small gift at your christening remember my dearest daughter that through me at this time you will be carried to Jesus Christ.“

This text is a revised excerpt from the article "Snapshots of the Past", first published in the 2021/22 issue of the research magazine EINBLICKE. Author: Deike Stolz