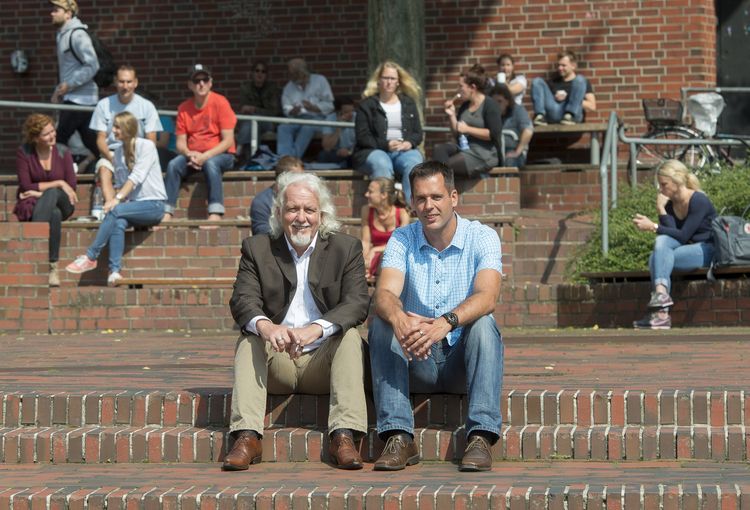

Self-tracking is in vogue: more and more people are gathering data about their bodies. Sociologist Thomas Alkemeyer and sport scientist Mirko Brandes are studying this phenomenon – each from a different perspective.

How many steps have I taken today? How high is my blood pressure? How many calories did I burn while jogging? More and more people are using apps, fitness armbands and smart phones to collect personal data about themselves and their bodies. This self-measurement trend is known as “self-tracking”. Oldenburg sports and social scientists are among those studying the phenomenon and its methods.

A visit to Dr. Mirko Brandes, Professor for Sport and Health at Haarentor Campus. The sports scientist uses self-tracking methods for his research. On his desk lies an inconspicuous-looking pedometer. It is actually a state-of-the-art device that contains an acceleration sensor and a microprocessor. The pedometer can be adjusted to precisely match the test subject's speed parameters.

Brandes and his team used the pedometer in a study on the rehabilitation of patients after knee and hip joint replacements. Their research was aimed at determining whether activity measures can help patients with new hip and knee joints to become more physically active and thus gain more confidence in their new joints.

In order to find answers Brandes and his team equipped their test subjects with high-performance pedometers and monitored them throughout the rehabilitation programme. Alongside the usual rehab therapy, participants received continual feedback from the sports scientists. In one-on-one conversations they evaluated the subjects' activity patterns and the number of steps taken daily. A follow-up examination of physical activity was carried out approximately three weeks after completion of rehab, in the subjects' home environment.

The first results of the study, carried out in cooperation with the rehab centre in Kreyenbrück, showed in the follow-up check in the home environment that subjects who had used the pedometer for the full duration of the study were more physically active than subjects in the control group. The latter had participated in an identical rehab programme but received no feedback and had only used the pedometer at the start and the end of the study. Furthermore the researchers demonstrated that subjects who made continuous use of the pedometer had a higher quality of life and are likely to trust their new knee or hip joints more than the other participants in the rehab programme.

Prior to their surgery, the subjects had often experienced permanent pain in their knee or hip joints over the course of many years, Brandes explains. “Using the tracking methods they could realize that their new joints could withstand continuous extra strain without causing any problems. Of course this motivates them be more active. And it boosts confidence in the new joint.”

Brandes sees another major advantage of self-tracking methods from a scientific perspective. In another experiment, “The Oldenburg Fitness Study”, he is analysing whether particularly inactive people who are put on specially designed fitness programmes actually start becoming more active. A key element of the study requires the subjects to record how much they move everyday using a pedometer over a two-week period. “In the past, we had to rely on questionnaires to gain information about physical activity in everyday life,” the sports scientist explains. But this data was biased by subjective limitations. Subjects tended to record how much they wanted to be moving instead of how much they had actually moved. “Through self-tracking the data is much more precise than it was in the past,” Brandes summarises.

But what does self-tracking do to people? And why are more and more people using these methods? Why are they putting their data online and comparing it with other participants in online forums? Are people not concerned about privacy? "We are careless with our data. We have yet to develop a cultural awareness of the ways such sensitive information can be used," explains the sociologist Thomas Alkemeyer. Alkemeyer sits two offices down from Brandes on Haarentor Campus. He is the spokesman of the postgraduate programme “Self-perception. Historical and Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Practices of Subjectification.”

Alkemeyer is interested in how an individual becomes a subject, and is thus made responsible not only for himself but also for the welfare of the “social community”. “Self-tracking is the attempt to self-optimise by permanently monitoring one's life through quantification. Thus the social norm of an unlimited capacity for improving performance, health and fitness is reproduced on one's own body. The individual subjects himself to this norm,” the sociologist explains.

One example is the Quantified Self movement initiated in 2007 by US journalists Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly. On the website quantifiedself.com self-trackers can discuss the latest data and developments on self-measurement. By now there are countless internet forums where self-trackers upload their collected data and compare such things as fitness levels with other self-trackers. Most well-known sport products brands offer apps that allow their users to compare data on physical activity.

“Subjectification is a double-edged sword,” Alkemeyer explains. On the one hand self-tracking helps people gain a certain control over their lives and allows them to live a reflexive life. On the other hand they are subjecting themselves to social expectations and entering into a never-ending competition with themselves and others. Self-empowerment comes at the price of self-subjugation.

For the sociologist, one of the reasons behind this development is that in modern society although the individual regards himself as autonomous, he always feels powerless in the face of external forces. “School education, vocational training, university – these things are less and less a guarantee for the future,” explains Alkemeyer. “There's no way of knowing whether what I'm learning today will have any relevance tomorrow.” At least, Alkemeyer says, this is how people today perceive their situation. The shift from providing to making provisions for the future, to a social state that is increasingly obliging the individual to be proactive is another factor. “Self-tracking promises that you can take charge of your own life. It offers you the chance to realise the modern ideal of being 'master' of your own self through your own body.”